An April 24, 1983 Los Angeles Times article by Howard Rosenberg headlined “Praise the Lord and lash the opposition” describes co-star of smash-hit TV drama Dallas Charlene Tilton emerging from a limousine outside Stage 43 of Hollywood’s Universal Studios.

Tilton — who played Lucy Ewing on one of the most-watched programs in television history — was there not on Dallas business, but to attend a studio taping of Pat Robertson’s The 700 Club for the Christian Broadcasting Network.

Meanwhile, that same week in the real Dallas, Iceman King Parsons teamed with David, Kerry and Kevin Von Erich to defeat the Fabulous Freebirds and Mongol in an elimination tag match as part of a World Class Championship Wrestling card.

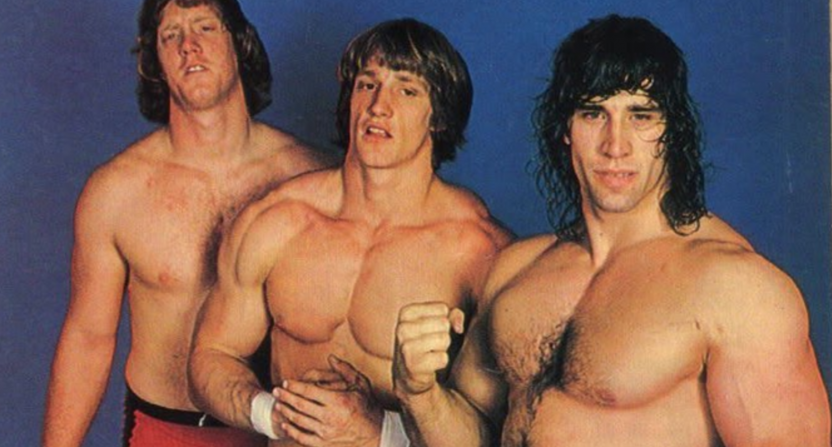

In 1983, the bad blood between the Von Erich family and the Fabulous Freebirds — a three-man outfit of P.S. Michael Hayes, “Bam Bam” Terry Gordy and Buddy Roberts — became the hottest storyline to come out of north Texas since the “Who Shot J.R.” arc on the 1980-81 season of Dallas.

The feud began on Christmas 1982 when Hayes — serving as special referee of the National Wrestling Alliance World’s Championship match between Kerry Von Erich and Ric Flair on the WCCW Christmas Star Wars card — instructed Von Erich to pin the champion Flair under unsportsmanlike conditions.

Von Erich refused as a good guy should, prompting Gordy to slam the door of the steel cage in which Kerry and Flair wrestled, thus setting off a firestorm for wrestling fans in Texas.

The Freebirds were ideal foils to the Von Erich family, coming in from Atlanta as mercenaries in search of the biggest paycheck. The brash, hard-partying lifestyle they represented is immortalized in an anthem that endured on message boards in the 2000s and on social media today.

The Freebirds’ arrogance and partying contrasted with the wholesome lifestyle the Von Erichs conveyed to the TV audience on KXTX-TV in Dallas, owned by Robertson’s Christian Broadcasting Network.

From the first broadcast of “Wrestling At The Marigold” aired on the DuMont Network in 1949, professional wrestling has been a reliable tentpole for television. And, in that vein, the story of World Class is impossible to tell without TV.

However, the way in which World Class revolutionized wrestling as it’s presented on TV is an enduring legacy of the promotion. Two documentaries on the Dallas-based federation — the sanitized, WWE-produced Triumph and Tragedy of World Class Championship Wrestling and the less varnished, highly acclaimed Heroes of World Class — both detail WCCW’s transformative legacy on broadcasting.

World Class introduced professional on-location video packages into its presentation, employed respected Dallas journalist Bill Mercer as play-by-play announcer, brought camera operators onto the ring apron to catch close-up action, and integrated pop music into the show.

WCCW provided a template for professional wrestling’s TV boom later in the 1980s, with the nationwide fame Hulk Hogan achieved in the decade’s latter half an extrapolation of the larger than life presence the Von Erichs had in Texas.

The most complete telling of the Von Erich story, including a more thorough examination of WCCW’s relationship with the Christian Broadcasting Network, is via The Lapsed Fan podcast. In its Lamentable Tragedy deep dive, the podcast explores the heroism of the Von Erichs in the ring as a conduit through which to spread religion to an audience that it may not otherwise reach.

That World Class, and by extension the Von Erich family, played in changing TV wrestling aired on a religious channel’s airwaves magnifies the tragedy of their story.

Among the ironies of WCCW airing on a Pat Robertson-owned station is that the 1982 angle that set off the promotion’s hottest drawing rivalry shouldn’t have occurred according to Robertson’s logic.

In 1976, the televangelist predicted the end of the world in 1982 and upped the ante with his 1980 guarantee of a full-on apocalypse.

Humanity, of course, endured beyond 1982. Sadly, the Von Erich dynasty didn’t last much longer than that with the first in a series of repeated tragedies in 1984. The death of David Von Erich in Japan in 1984 began a horrific, nine-year stretch defined by loss.

The decline of the Von Erichs is one of the more well-known stories among wrestling fans, and the story gains a new audience in December 2023 with the release of the Sean Durkin-directed biopic, The Iron Claw.

In the years that followed World Class’s peak with the Von Erichs vs. Freebirds feud, it became increasingly clear the Von Erichs on TV were not representative of the real-life Adkisson boys.

For as long as wrestling’s been a TV product, it has at its heart been a morality play.

American wrestlers vanquishing Soviet villains was a popular trope throughout the Cold War, for example — and, on the other side of the world in the years following World War II, Rikidozan became a Japanese folk hero for defeating American challengers.

This being a form of entertainment, of course, the stakes were contrived and the combatants played roles. Check out footage from “The Russian Bear” Ivan Koloff’s peak in the 1970s, and he sounds suspiciously more French Canadian than Russian.

So that the blood feud between the hard-livin’ Fabulous Freebirds and clean-livin’ Von Erichs was not reflective of reality is nothing out of the ordinary. But that so much of the rivalry played out on the Christian Broadcasting Network, with the Von Erichs’ touting lives of virtue while the Adkissons were mired in turmoil, made for an especially damning betrayal of the family’s fans.

A 1988 D Magazine article and a Penthouse story that same year shared with the public sordid details of Von Erich boys’ struggles with drug abuse and the mysterious circumstances surrounding David Von Erich’s death; as well patriarch Fritz’s domineering personality and the suicide death of Mike Von Erich.

The D Magazine piece is made all the more tragic when one considers it ran three years before Chris Von Erich died by suicide in 1991, and Kerry Von Erich took his own life in 1993.

Kevin is the last surviving brother, returning to the squared circle in the Dallas area on Dec. 16 to accompany his sons, Marshall and Ross, in an All Elite Wrestling bout.

A personal aside, I have sympathized with the Von Erich boys for as long as I’ve known their backstory. I am a survivor of familial suicide, losing my brother four days after my 13th birthday. No one is an inherently bad person for struggling with addiction, as some of the Von Erichs had, or for lapsing into seemingly inescapable depression as three of the four deceased Von Erichs did.

In the world of professional wrestling, which existed as a storytelling medium of Good vs. Evil without nuance — particularly in the 1980s — the complexities of personal struggle don’t fit, however. The Von Erichs could only be fan favorites if they were presented as without moral failing, and especially so on a TV home such as theirs.

Wrestling’s track record with its handling of real-world issues hasn’t done the medium favors in attracting new audiences. Bob Costas balked at a scheduled appearance at the former World Wrestling Federation’s Wrestlemania VII event when the run-up to the main event between Hulk Hogan and Sgt. Slaughter centered around the war in Iraq.

Costas telling Alex Marvez for The Miami Herald in March 1991 that “I didn’t think [appearing at Wrestlemania in Los Angeles] would be in the best of taste” provides an interesting backdrop for the heated exchange between the sportscaster and longtime WWE head Vince McMahon exactly one decade later on HBO.

McMahon’s WWE also garnered unfavorable response when it tackled same-sex marriage in 2002 with its ill-fated Billy & Chuck wedding. In 2005, when a wrestler portraying an American of Arab descent, Muhammed Hassan — the wrestler himself was not of Arab-American lineage — carried out an attack on The Undertaker that left far too much like the video-taped murder of journalist Daniel Pearl.

These misguided attempts at allegory also demonstrate, however, that wrestling also hasn’t shied away from sensitive topics. The aforementioned America vs. USSR feuds that were omnipresent in every territory during the Cold War as well as Rikidozan’s rise in Japan played on geopolitics, after all.

Fritz had, himself, taken on the Von Erich name while portraying a pro-German villain in the early 1950s — which, given the timeline, the connotations are self-explanatory.

Religion has been much murkier water that wrestling hasn’t often waded into. All Elite Wrestling came under fire earlier this year when, as part of World Champion Maxwell Jacob Friedman’s feud with the villainous Bullet Club Gold, heel wrestler Juice Robinson threatened to bunch the Jewish MJF with a roll of quarters.

The quarters called back to antisemitic abuse MJF said in a previous segment on AEW TV he had experienced in his youth.

The poor reception of the storyline implicitly explains why religion doesn’t often play a part in wrestling’s morality stories. And lest anyone attribute the backlash to the AEW segment to 21st Century sensitivities, consider the Florida territory in the same timeline as the Von Erich’s rise to stardom in Texas.

There in Florida, where David Von Erich wrestled as a bad guy in 1981, Kevin Sullivan formed a stable of heels in the ‘80s that practiced bizarre, pre-match rituals and spoke with an ominous air of mysticism.

The allusions were clear, but only implied — until a magazine cover featuring Sullivan ran with the headline “Satan Is My Manager.” Sullivan has repeated in interviews for years since that he intentionally avoided specific references to satanism or Christianity due to the very real emotions it invoked in the audience.

Likewise, the religious underpinnings of the Von Erich family’s rise perhaps exacerbated the harsh dichotomy of the wrestling heroes and the tormented people who portrayed them.

In that sense, the allegory of the Von Erich’s decline was less the straightforward tales of Good vs. Evil typically presented in a wrestling ring. Rather, their family tragedy paralleled the facade of 1980s televangelism that cracked throughout the decade, from Robertson’s ill-fated doomsday forecasts to the litany of crimes for which Jim Bakker was convicted.