Fifteen years ago today (August 30th, 2007), the Big Ten Network launched to modest fanfare and expectations. What’s now one of sports media’s biggest success stories of this century was mostly thought of back in 2007 as a very risky and iffy proposition for the Big Ten and Fox, the conference’s partner in the venture.

At the time of the launch (and for almost a year), the fledgling network couldn’t be found on most major cable providers like Time Warner, Comcast, Charter, Mediacom and Dish. Despite a rocky first year in which fans and even coaches lamented the network and it’s lack of distribution, it didn’t take long for the network to emerge as a runaway success and one that other conferences and professional leagues would quickly look to emulate.

Fifteen years later, the implications of the network are still being felt today as the Big Ten continues to expand, with the additions of USC and UCLA set to bring the network to millions of homes in the Southern California area and with other schools believed to be added down the road. Meanwhile, the Big Ten recently announced it will become the first Power Five conference to forgo any broadcast relationship with ESPN, instead opting to partner with a powerful triumvirate of CBS, NBC, and Fox (who has, over time, upped their ownership percentage of the network to 61 percent).

Outside of the Big Ten, expansion and realignment continues unabated across college sports. And other Power Five conferences, as well as professional leagues, have followed the Big Ten’s lead in launching their own networks, with some more successful than others.

Needless to say, the Big Ten Network’s launch was by a large margin, one of the most impactful events in all of sports (and not just sports media). And not only for the conference itself, but for Fox, ESPN, the many schools impacted by realignment, and the many other dominoes that subsequently fell both in sports and in sports media. Below, we look at the historic origin of the network.

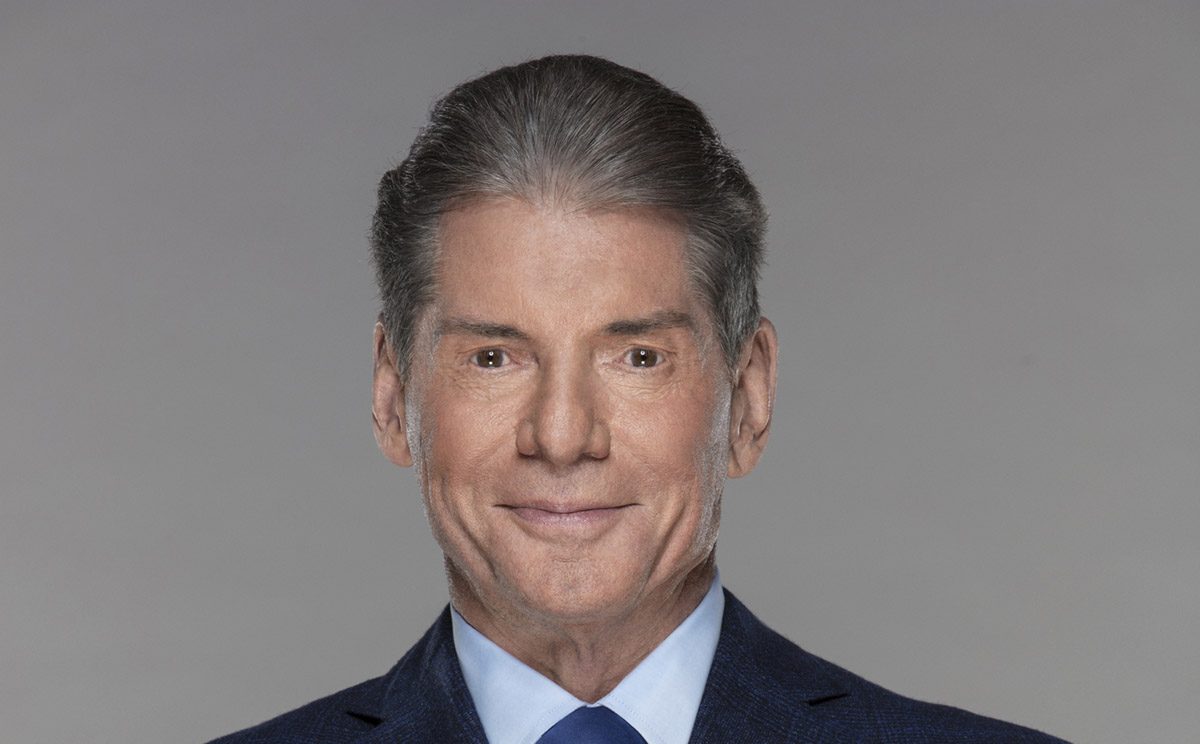

“He was very demanding – “take it or leave it at the table,” that kind of thing. He got off on that. Oh, he loves confrontation.”- Ross Greenburg, President HBO Sports

As ESPN faces the soon-to-be reality of losing the ratings juggernaut that is the Big Ten, one can only imagine the amount of regret the network has the Big Ten Network even came to be. The launch of the Big Ten Network would go onto serve as the origin of now flourishing Fox and Big Ten relationship and be Fox’s return to big-time college football after a disastrous stint airing the BCS. Former ESPN president John Skipper lamented the implications of the Big Ten Network’s launch in a recent South Beach Sessions podcast episode.

“We should never have let the Big Ten Network happen at ESPN. Wasn’t good for our business that those games leaked out of the system. But Jim Delany had the smart idea to launch a network with FOX and that also was good business, even though it had a rough start.”

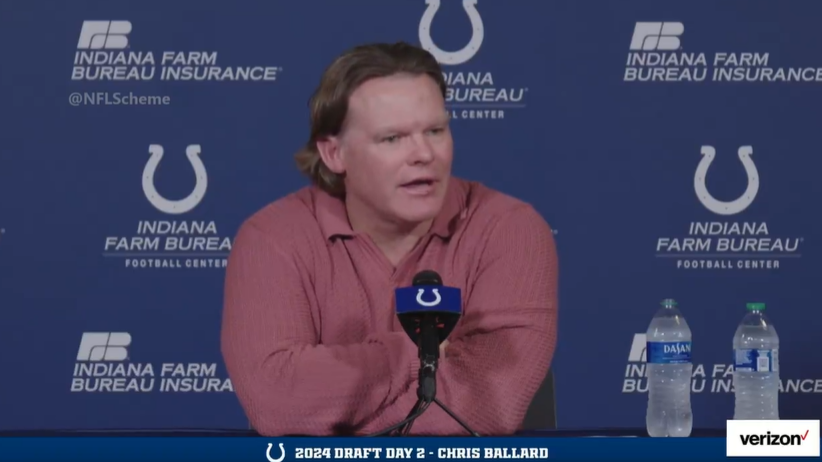

How did this happen? Before getting into that, it’s good to get a feel for just who was leading negotiations for ESPN at that time. Mark Shapiro was ESPN’s up and coming executive vice president for programming and production at the time. Despite his young age (at the time in his early 30’s), Shapiro had developed quite a reputation as being brash and confident as well as eager to experiment with non-live event programming such as PTI, Tilt, and Playmakers.

Shapiro seemed to favor the idea of creating shows sports fans would watch which would make the network less dependent on acquiring live rights from leagues and conferences. Because of this he was known as a VERY aggressive negotiator when it came to live rights acquisitions. A few highlights on that from the bible on all things ESPN, Jim Miller and Tom Shales’ Those Guys Have All The Fun.

Fred Gaudelli, executive producer of NBC’s NFL coverage

“When Mark came in, he brought an arrogance. His regime or style, however you want to put it, was basically the turning point for ESPN going from the good guy to the arrogant guy. I don’t care what they tell you, ESPN is not well liked at 280 Park (NFL headquarters], they are not well liked at the NBA, and they are not well liked at Major League Baseball. So you saw it in their relationships with partners, and you saw it on the air with the way they over-promoted the stupidest things, like the Bobby Knight movie. And that’s what Mark brought into the company.”

“Mark Shapiro ran a dictatorship, and ESPN still suffers from it today.”

Barry Melrose, ESPN NHL analyst

“Shapiro and Bettman came to hate each other. And Gary is a lawyer and a tough negotiator, and I think he felt that ESPN was trying to take advantage of the NHL and lowball them with the price.”

Ross Greenburg, president, HBO Sports

“He was a bulldog negotiator, and in talking to league people, you would hear stories about how he was very demanding – “take it or leave it at the table,” that kind of thing. He got off on that. Oh, he loves confrontation.”

And from the man himself, Mark Shapiro

“I wanted Wimbledon badly because it was a Tiffany product that would enhance the image of ESPN yet simultaneously be an innings eater-two weeks, lots of hours, particularly in the morning. Bill and I cut a five-year deal at six million per year. What I’ll member most about closing that deal was that after Bill and I finished our slugfest, he got up to leave and the back of his shirt was completely drenched, from the collar on down. It was as if he just got out of a pool. I felt such a sense of satisfaction and victory.”

As ESPN and the Big Ten neared the natural negotiating window for a new contract, Mark Shapiro would find himself opposite a much more game opponent in his next planned “slugfest”.

“Consider Them Rolled”- Jim Delany, Big Ten commissioner

The impetus of the Big Network tracks back to one infamous meeting on April 30, 2004. Despite the historic nature of this meeting, the story was largely unknown until the Chicago Tribune‘s Teddy Greenstein wrote his 2011 article titled “ ESPN’s lowball offer triggered Big Ten expansion”.

An amiable session in which the Big Ten and ESPN cleaned up “housekeeping matters” — schedules and announcers — took a nasty turn at the one-hour mark. That’s when talk turned to a contract extension, a negotiating session that went nowhere. Fast.

“The shortest one I ever had,” Delany told the Tribune. “He lowballed us and said: ‘Take it or leave it. If you don’t take our offer, you are rolling the dice.’ I said: ‘Consider them rolled.’ “

Delany had warned ESPN officials that without a significant rights-fee increase, he would try to launch a new channel that would pose competition both for TV viewers and the Big Ten’s inventory of games: the Big Ten Network.

“He threw his weight around,” Shapiro said in a telephone interview, “and said, ‘I’m going to get my big (rights-fee) increase and start my own network.’ Had ESPN stepped up and paid BCS-type dollars, I think we could have prevented the network. In retrospect, that might have been the right thing to do. Jim is making a nice penny on that.”

Said Delany: “If Mark had presented a fair offer, we would have signed it. And there would not be a Big Ten Network.”

And just like that, the first domino fell that has arguably led to dozens of college programs switching conference affiliation and one of the more central causes why your cable or satellite’s monthly bill has steadily increased since.

I recently spoke with Greenstein (an expert on all things Big Ten related), who shared some additional insights on the personal dynamics that played such a crucial role in that meeting.

“You’ve got this Mark Shapiro in his early 30s and trying to establish himself and “Oh I’m the tough guy and these guys are not gonna push me around.” So you’ve got these two forces with their huge egos and Jim had the leverage. He had obviously looked into it enough to know it was viable. He knew it would be really hard, but he had at that point probably knew if we do this maybe we are going to partner with FOX. If we partner with FOX I think we’ll get DirecTV.”

“Will we have a conflict with Comcast? How will we get through it? I think he believed in himself enough to think “Okay, I can get through this.” So I think he went into that with ESPN thinking “All right, this is going to happen, and we will get a nice increase and things will be fine.” But every smart guy goes into a negotiation thinking ‘What if,” and he had the what if in his back pocket.”

Delany spent much of 2004 and into 2005 convincing skeptical university presidents and athletic directors of the viability of such a plan, and that it wasn’t just being investigated and pursued to create leverage for ongoing negotiations with ESPN. In early 2006, the framework for the conference’s relationship with Fox began to take root, as Scott Dochterman recently explored at The Athletic.

“We did have a napkin,” Delany said. “And we did map out in general, on that napkin, how the programming might look in a football season, in the spring Olympic season and in a basketball season. We were going from maybe a couple hundred games under the ESPN/CBS umbrella to the potential of a network that would be operating 24/7/365.”

“How we could do this, and how we could get us the Fox distribution arm?” Jones said. “The most important thing in trying to start a network is distribution and how the economics could work. We kind of shook hands and said, ‘Let’s see if we can start this.’”

Shapiro left ESPN in late 2005. That led to an attempted renegotiation. Per The Athletic, “ESPN officials came back to Delany late in the process to persuade him to drop the network plans and renegotiate the syndicated rights. He declined.”

By then, it was too late. And the rest is history.

Success brings upheaval and change

At a high level the Big Ten Network’s successful launch validated that there was a viable and lucrative business model for professional leagues and conferences to carve out and package third-tier sports rights (games mostly not highly sought after by national networks) and put them all on one channel. The idea that cable providers would pay for such a channel was at the time a hypothesis that hadn’t yet been tested. Some more local channels have tried and spectacularly failed in this endeavor.

As the Big Ten Network was almost universally added to cable systems in the Midwest and beyond, it didn’t take long for other pro leagues and conferences to get the memo—you were leaving money on the table by not having your own network. Not only that, but the race was onto add schools to help you get the channel into more households across the country, and thus reap more per-subscriber fees. The Athletic’s series on the Big Ten Network outlines this strategy, which has now become college football’s guiding principle when it comes to expansion.

“For BTN, it was a chance to enter Philadelphia, New Jersey, Washington D.C., Baltimore and New York City. Then-BTN president Mark Silverman called the expansion “a different kind of reasoning.”

“Usually, you expand to bring in a premier program athletically,” said Silverman, who ran BTN from its launch in 2007 through 2018. “Nebraska was more of a brand play than a population cable-homes play.

“Rutgers and Maryland, I think the three or four objectives there were to spread the Big Ten into a new area that would help with recruiting and help with being a dominant college conference in a very populous part of the country. It was to get BTN subscribers.”

The conference television money arms race was now on. As noted by The Athletic:

“Through BTN guarantees, the 11 schools’ conference payouts grew from $10.7 million during the 2007 fiscal year to $18.45 million in 2008.”

When Shapiro and Delany sat down in 2004, schools from all power six conference were all getting television money in the general ballpark of each other. Ticketing revenue and donations was significantly more important to the schools. That changed with the launch of BTN and suddenly schools with attractive brands, and or attractive television markets, were suddenly having to consider their options in terms of conference membership. The gulf between conference TV money only widened further as schools chosen for reallignment would up and leave for more money, but their departure usually only further kneecapped the existings conference’s ability to secure lucrative television contracts (the situation the Big 12 is now facing with Texas and Oklahoma departing as well as the Pac 12’s with UCLA and USC leaving). The rich got richer and the bleeding hasn’t stopped yet.

Navigate projects SEC and Big Ten per-school payouts will be $40-50 million clear of rest of Power Five by 2026 https://t.co/oQNVAWeXAF pic.twitter.com/7xx8AatZur

— Awful Announcing (@awfulannouncing) March 15, 2022

Pro leagues also took note as well, taking more of their games off of local channels and national channels and plopping them onto their newly created networks, hoping to follow in the footsteps of the Big Ten and forcing cable companies to carry their channels as well.

The direct and indirect fallout from the Big Ten Network’s success today is truly staggering. It can be tied to an ever-expanding list of developments spanning sports media and sports itself, including:

- The launch of the NHL Network in 2007

- The launch of the MLB Network in 2008

- NFL Network winning carriage battles with Comcast and Time Warner (2009-2012), mostly through the increase of games broadcasted on the channel on Thursday nights.

- ESPN largely abandoning having major college football games on Thursday Night because of the NFL’s newfound dominance in that time slot on NFL Network.

- Nebraska joining the Big Ten in 2011 and the subsequent creation of the Big Ten Championship game in 2011

- ESPN announcing the Longhorn Network in 2011

- Fox broadcasting regular season college football in 2011, breaking ESPN’s near monopoly on the sport. Fox would over time add games for the Big 12, Pac-12, and Big Ten.

- Fox’s return to college football and basketball helping springboard the launch of FS1 in 2013.

- The launch of the Pac-12 Networks in 2012

- Utah and Colorado joining the Pac 12 in 2012 and the subsequent creation of the Pac 12 Championship game in 2012

- Texas A&M and Missouri joining the SEC in 2012

- The Big 12 adding TCU and West Virginia in 2012

- Syracuse, Pittsburgh, Notre Dame joining the ACC in 2013

- The Power Six becomes the Power Five in 2013 with the splitting off of the Big East from the newly-created American Athletic Conference

- Louisville joins the ACC in 2014

- Maryland and Rutgers join the Big Ten in 2014, giving the conference and network a prized northeast corridor including New York, Baltimore, Washington DC, and Philadelphia

- ESPN launching the SEC Network in 2014 (wholly owned by ESPN).

- ESPN launching the ACC Network in 2019 (wholly owned by ESPN).

- BCS scrapped in favor of the College Football Playoff, which creates a four team playoff with all games airing on ESPN.

- ESPN doubles down on their SEC relationship, announcing they’ll add CBS’s SEC game of the week starting in 2024.

- Texas and Oklahoma announce they’ll join the SEC in 2025 or perhaps even earlier.

And from the last year:

- The Big 12 announces they’ll add BYU, Cincinnati, Houston, and UCF

- AAC raids Conference USA, announcing they’ll add Charlotte, Florida Atlantic, North Texas, Rice, UAB and UTSA

- USC and UCLA announce they’ll be joining the Big Ten

- The Big Ten announcing their new $1 billion a year-plus deal with Fox, NBC, and CBS, severing their fruitful long-term relationship with ESPN.

That’s not even a full list, and we’re not even close to done. The fates of the Big 12, Pac 12, and ACC are all very much up in the air as the SEC and Big Ten continue to dictate the future of the sport. There are plenty of dominoes left to fall. Has the subsequent fallout been good for college football and for sports media itself? For some like Fox, the Big Ten, and SEC the answer is an obvious yes. While ESPN is losing their relationship with the Big Ten, the creation of the SEC and ACC Networks may just have them ahead in all of this change as well. For fans of schools in the former Big 12, Pac 12, ACC, the former Big East and non P5 conferences, it’s hard to argue any of this disruption has made things any better.

I asked Greenstein on how he views the fallout from the fateful day in Chicago in 2004.

“Yeah, it was the catalyst. And it’s just fun to speculate. Would Scott Frost be at Nebraska? Would Nebraska be better if it was still in the Big 12? Would USC and UCLA be joining the Big Ten? There is probably no way Maryland and Rutgers are in the conference. It’s two men, Jim Delany and Mark Shapiro, and they are sort of battling it out over who has the bigger manhood. And as the result of that, all these things have happened, and it’s fun to speculate what would have and what wouldn’t have. Wildly successful, super rich. But we all make mistakes, we all have hubris and ego, and I think it might have gotten the best of them. “

For better or for worse the fallout of the day is hard to wrap your head around and may still take a few more decades to be fully felt. Looking back, it’s hard to think of a bigger butterfly effect moment in sports media.