Getting beaten to a good scoop by a competitor is often one of a reporter’s worst nightmares, and there have been some memorable instances of that in the sports world.

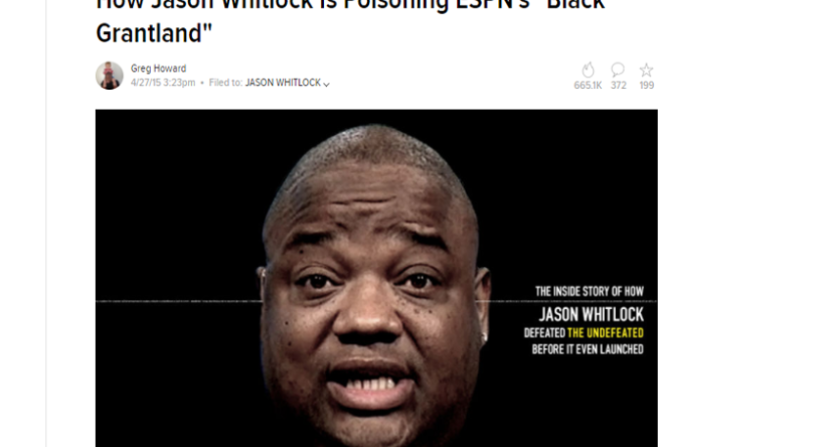

Elon Green recently collected some memorable stories from prominent reporters on times they were scooped for the Columbia Journalism Review, and there are a couple with a significant sports component, including Greg Howard (now at The New York Times, previously of Deadspin) talking about how his current employer beat him to the Jason Whitlock Undefeated playbook story (which Howard went on to own regardless), and Joel Anderson (of BuzzFeed) talking about how he lost the scoop on Michael Sam coming out to ESPN and The New York Times.

Current sports reporter Don Van Natta Jr. (of ESPN) also shares a story from his previous work as a New York Times investigative reporter, on how a Clinton administration source played him on the delivery of a subpoena. It’s the Howard and Anderson stories that have the most sports connections, though, and in both cases, losing the scoop may actually have led to better later stories. Here’s the key part from Howard’s story:

When I was at Deadspin, Richard Sandomir, who’s now my colleague, beat me to Jason Whitlock’s playbook. I’d been working on a thing about The Undefeated and somehow ESPN basically rolled out the red carpet for Sandomir, and he went to Bristol, hung out with Jason Whitlock, and saw the playbook, which is their blueprint for what the site would be.

We momentarily panicked because we had so much stuff. We had people leaking to us and we thought we had a whole lot of exclusive shit. And it turned out that maybe because ESPN knew we were on the story, they went to The New York Times and they just unloaded. Here’s the playbook.

Obviously, I have a different sensibility than Sandomir. I’m black and young, and I have a different personal relationship with Jason Whitlock. I was coming at the story from a different place, with different reporting imperatives. I saw the playbook for what it was—the work of a megalomaniac.

But initially we panicked, and then we read the story and it was like, Oh, shit! Oh, shit. They like [the playbook]. And by this time, we had begun writing our story. I will never forget thinking, Holy shit, we just got scooped by The New York Times. But it was okay because, because it allowed us to punch up even more. The fact that we were able to point to the Times and say, See? They loved it, was, for us, a coup. It became part of our own narrative.

The latest

- Could NFL see next Saudi sportswashing controversy?

- ESPN and NBA have reportedly ‘essentially come to terms’ on deal that would keep Finals on ABC

- G/O Media sells The Onion to ‘Global Tetrahedron,’ ex-NBC reporter Ben Collins to serve as CEO

- Eli Gold on Alabama exit: ‘You can’t argue with city hall.’

As I remember it, from both memory and an old email thread, we were making arrangements to talk with one of Sam’s former college teammates and subsequently reached an agreement with his handlers to not “out” him in our publication. There were some serious internal discussions in a very short amount of time about not “outing” Sam in a reckless and irresponsible manner, and for that I have to credit our incredibly diverse and thoughtful staff for helping us navigate those issues. Instead, we’d wait until he made the announcement on his own terms and then immediately publish our own pre-written and pre-reported story.

Well, it didn’t quite work out that way: Sam and his handlers, realizing that the story might get out anyway, made their announcement that night in coordination with ESPN and The New York Times.

That, uh, obviously hurt. And though we ultimately got credit in at least one published account for pushing the announcement, the fact is that we—but mostly me—still got beat on one of the biggest sports stories of the decade.

The silver lining is that our interest in and handling of that particularly story led me to what I think is the best story of my career: a lengthy look at Sam’s tortured relationship with his family, particularly his father.

It’s notable that both these stories may actually have been improved by losing the scoop. Howard’s April 2015 piece on Whitlock was an incredible indictment of the latter’s management style and what he was doing at The Undefeated, and it played a major role in Whitlock being ousted as head of the site in June and then leaving for Fox that October (where he started his tenure by blasting Howard and Deadspin).

Having the existence of the playbook already out there in some form may have helped Howard’s story focus in more on the details inside it, and on employees’ reactions to it. Similarly, Anderson’s nuanced and detailed piece on Sam’s relationship with his father that October was only possible because BuzzFeed was respectful to Sam and his camp and how they wanted to make that announcement.

So, not being the first to report something isn’t always a negative. That’s perhaps especially true if it can let you be more focused on what’s really interesting, and look in greater detail at a particular element of the story. It’s also worth noting that scoops often don’t have huge shelf lives these days, so getting one isn’t the be-all and end-all of reporting, and losing one isn’t always the worst thing in the world.. But it’s quite notable to see these prominent journalists (and many others more on the news side) talk about how they lost scoops, and how they adapted afterwards.