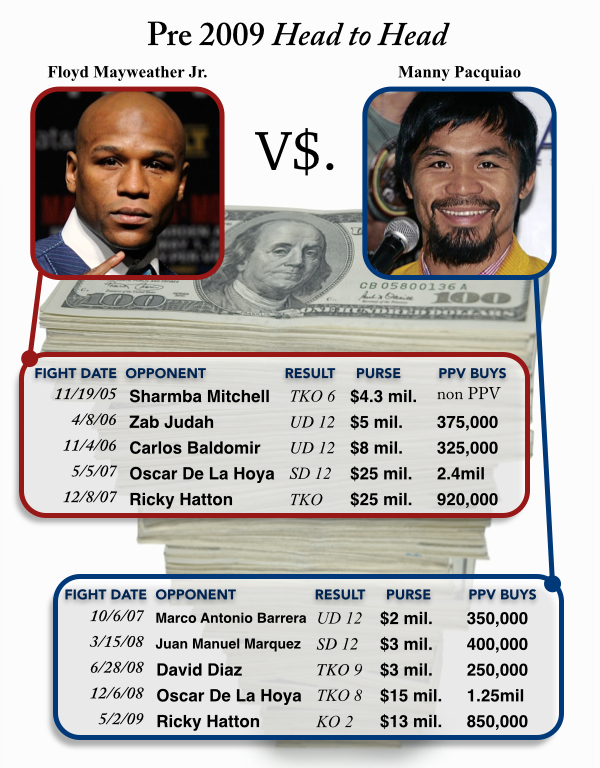

That 2009 skirmish between Kenny and Mayweather had a prelude. In 2006, Mayweather was lining up a weight class jump against Zab Judah, considered the true, lineal champion at welterweight and the owner of multiple major sanctioning organization title belts.

“He was the welterweight champion of the world,” Kenny recalled. “A funny thing happened on the way to the title fight: Zab Judah lost to Carlos Baldomir. Most everybody in boxing thought, there goes that fight.”

Instead, Baldomir, a minor figure in boxing until he shockingly beat Judah, was only able to afford the sanctioning fee for one of the belts. Despite losing to Baldomir, Judah remained, by virtue of Baldomir’s relative poverty, the IBF welterweight “champion” and the fight with Mayweather was set for the summer of 2006.

Just prior to their interview live on ESPNews for The Hot List, the veteran anchor saw something that raised his hackles.

“The promoter, I saw in their press release – I think it was Top Rank at the time – starts calling it the welterweight championship of the world. In my head I’m thinking , oh no they’re not. C’mon, we know better,” Kenny said. Usually in interviews, boxers would acknowledge that a title didn’t equal being the real champion.

“Real champions don’t have to fake it,” he said. “I’m thinking Floyd being a real champ, at 130 [pounds], at 135, is not going to try to fake it. It defies logic. It defies reality. Sure enough when I asked him about it, he started telling me it was. I know he’s acting in his interest, in his short-term interest, but that’s not my job. My job is, the fight with Zab Judah is good, but just don’t tell me it’s for the championship.”

Before that contentious interview, Kenny and Mayweather had always been on good terms according to the anchor. In fact, Kenny had kept an autographed copy of KO Magazine that Mayweather had signed, “To the #1 broadcaster, Brian Kenny.” As host of Friday Night Fights, Kenny had interviewed Mayweather numerous times and attended many of his fights.

“I had always thought he was vastly underrated on the way up,” Kenny said. “He was. He was underrated and underpaid.”

Despite the heated live back and forth, Kenny left the interview with no sense that Mayweather was angry. After the segment concluded, Mayweather and Kenny shared a laugh, Kenny said, and Mayweather repeated what he said on the air: That Kenny could be the Howard Cosell to his Muhammad Ali.

But Kenny later surmised that Mayweather soured on the interview.

“I think he was good with it, but afterwards when it gets a life of its own, people start getting into your ear saying things,” Kenny said. “He enjoys the verbal sparring. Right after we were doing it, he had no problem with it. He loves the engagement.”

So by 2009, Mayweather was primed for a rematch. Kenny made sure he got the assignment, as he did for all boxing interviews by the time he had moved over as a regular at SportsCenter’s 6 p.m. ET slot. Other SportsCenter anchors didn’t follow boxing as closely as Kenny did, and ESPN’s other boxing specialists, Teddy Atlas and Max Kellerman, weren’t stationed in Bristol.

Kenny said he would always come in early when a boxer was making rounds via satellite to promote a fight. On the day of Mayweather’s interview with Kenny, May 20th, everyone had a sense sparks might fly, Kenny said, based on the previous encounter.

And when they started flying, ESPN producers let them fly freely.

“Normally, you do those things and they’re five, six minutes. This went on a bit longer,” he said. “I think we all kind of knew it might be something. My producers at the time knew I would kind of handle it. I knew the subject matter. I knew the interviewee. There was not a lot of traffic in my ear. You’re always concerned about time. In this case it was OK – the sense was, go to work, go ahead and talk to him and let’s let it go.”

Kenny began provocatively. Mayweather had retired as the consensus top pound-for-pound boxer, an unofficial designation for the best fighter in the world regardless of weight. Kenny introduced Mayweather as the “former #1 pound-for-pound fighter in the world.” Mayweather balked immediately.

“He had retired. I do follow a certain protocol. Was I tweaking him a little? I’d be lying if I didn’t think it would stir some reaction,” Kenny said.

Aside from that “opening jab,” Kenny said, he didn’t go in intending to start a ruckus.

“The best interviews that occur, and I’ve told this to a lot of people about those two interviews with Floyd, you need to go in not picking a fight, you need to go in asking open-ended, lean, neutral questions and let them answer,” he said. “If you see my questions, my questions are fair.

“I’m just asking him, why wouldn’t you fight the champion in your own weight class? He said he’s the #1 cash cow. I ask, what about Oscar De La Hoya? You’ll see, I’m not being belligerent, I’m being persistent,” Kenny continued. “I’m not combative. It’s more of a Zen approach. I’m trying to be fair but I’m persistent and I’m dogged. Yet I wanted him to answer the question. I asked a question and he never answered.”

The biggest of those questions was THE question on the minds of every boxing fan, and, increasingly, the general sports fan, too: Would Mayweather fight Pacquiao?

* * *

Into the void left by Mayweather’s retirement in 2007 stepped Pacquiao, who already had been nipping at Mayweather’s heels in boxing fans’ rankings of the pound-for-pound best in the sport.

The notion that a Filipino who spoke little English would turn into boxing’s flagbearer occurred to very few, but Top Rank had done an excellent job of getting him into position for it.

There was no doubting the in-ring results: His signature wins were over all-time great Mexican fighters Erik Morales, Marquez and Marco Antoio Barrera, in bouts that were either almost preposterously action-packed, or else one-sided awe-inducing blitzkriegs. Mayweather was the cool virtuoso, inspiring gasps by those who appreciated his acumen; Pacquiao was a cyclone of violence that required little grasp of nuance to enjoy on a visceral level.

Unfortunately for Pacquiao, he was doing his damage at 135 pounds and below, having started his boxing career as a starving street urchin who weighed 106 pounds in his pro debut at age 16. The lack of a dominant, charismatic American heavyweight tends to hurt the sport domestically, but at times, fighters as small as welterweight have filled the gap, such as when Leonard, Roberto Duran and Hearns stole the spotlight from Larry Holmes’ reign over the moribund big man division.

Yet Pacquiao had proven he could sell despite his size, in 2008 breaking the PPV record for fighters below the welterweight limit. And left at the altar by Mayweather, De La Hoya needed a new partner.

When talks began for De La Hoya-Pacquiao, the response from boxing fans was mixed at best. Pacquiao would jump up two whole divisions to welterweight to fight a man who himself had previously competed two whole divisions above that at middleweight. The fight appeared to many more like a sideshow than a legitimate contest.

Pacquiao would go on to slaughter De La Hoya and send him into retirement.

In Pacquiao, boxing had a new pound-for-pound king who was the anti-Mayweather. He gave his money away to nearly any Filipino who asked rather than buying new Lamborghinis; he fought like a force of nature rather than a methodical prodigy; he would not speak a word of vanity, instead living by the motto he uttered before his recent rematch with Timothy Bradley: “Those who humble himself will be exalted, and those who are exalted will be humbled.”

Pacquiao’s steamrolling of a man that Mayweather beat in a less destructive fashion, De La Hoya, fueled a clamor for Mayweather’s return.

CLICK HERE TO CONTINUE READING 12 BRUTAL ROUNDS ON SPORTSCENTER

Comments are closed.