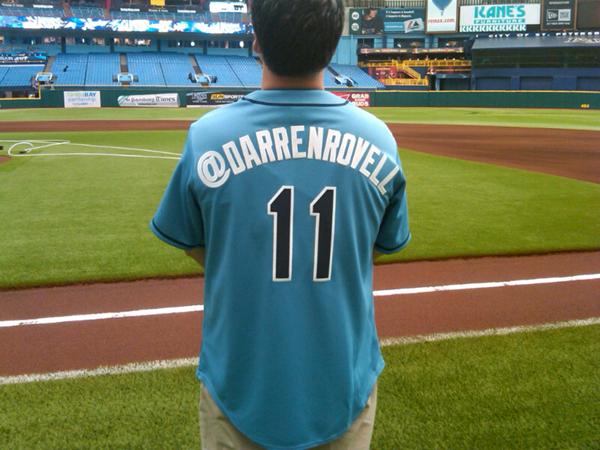

Darren Rovell of ESPN is one of the foremost authorities on sports business in America, building a personal brand over the last ten years that, with occasional hiccups, is rivaled by very few in his subset of our industry.

As with many ESPN personalities, Rovell’s immense popularity on social media has made him countless enemies. The more followers Rovell collects on Twitter—he’s up to more than 755,000 at the time of this posting—the more people seem to turn on him.

Outside of perhaps only Donald Trump, Rovell leads the planet in “delete your account” responses, with silly puns like this turning people’s stomachs:

The Dallas Cowboys have quickly turned into the Dallas Owboys #Injuries

— Darren Rovell (@darrenrovell) October 5, 2015

That post garnered 496 retweets and 502 favorites. The Twitter “engagement” metrics Rovell often touts as internet equity must have been off the charts for that tweet. And yet, most of the comments were, shall-we-say, not kind.

The thing is, while most in sports media don’t like Rovell, we know that if Adam Jacobi (the once and future king of sports media internet puns) had posted the same joke, we would have hated it for all the right reasons.

If PFT Commenter had posted it, he’d probably get another book deal.

When Rovell posts it, everyone wants him to go away forever.

It’s almost sad. The internet feels Rovell’s status in the industry and role at ESPN should preclude him from making such puns, or tweeting ad nauseam about state fair foodstuffs. He is a sports business reporter, so report about sports business.

But is it fair to Rovell the human—note: I have yet to verify if @darrenrovell is actually a human or just a never-ending Twitter algorithm uploaded to the cloud—that some of us are allowed to be serious and silly and three dimensional in a digital world, but he isn’t?

Is it just because he’s not very good at it that we so often want him to delete his account?

The answer is no. No to everything. No, you shouldn’t feel bad. No, it’s not sad. No, no, no, because Rovell did this to himself back on July 14, 2011.

This is his own fault.

Rovell was still working for CNBC as a sports business reporter in the summer of 2011 when he posted an article titled, “The 100 Twitter Rules To Live By” to commemorate reaching 100,000 followers on Twitter.

The post was one of the most poorly received pieces of writing/reporting/journalism in the history of the medium. Rovell became a lightning rod from that moment forward, and the more and more followers he collected, the more bewildered the rest of sports media became.

(Full disclosure: around that time I was working with the organizers of the sports media conference BWB on an awards project during which I presented both Rovell and Sports Illustrated’s Richard Deitsch with the “Best Sports Media Tweeter” award. It was a tie, as a hand-selected committee of insiders had chosen Deitsch, while the popular vote tabbed Rovell. At the event, Deitsch gave a thoughtful speech about the power of social media in sports. Rovell stood silently on the stage, tapped into his phone before holding it up triumphantly before walking off to abject confusion from those in attendance. Rovell thought his tweet would instantly pop up on the screen behind him, and figured everyone in attendance was following him anyway, so they would get his “acceptance tweet” in lieu of a speech. It was the perfect Rovellian moment. And yes, the trophies were customized Muppets for each winner.)

It’s fun sometimes to go back to Rovell’s 100 Twitter rules to think about what he’d change now. Twitter is an evolving beast, so many of his rules no longer apply given the shifting landscape of social media and the technological advancements over the last four years.

And yet, many of his rules were actually kind of good then, and still ring true today. So why does Rovell consistently break them?

By my count, of the remaining relevant rules Rovell penned back in 2011, he goes against more than a dozen with regularity. Here are 15 I pulled that Rovell created yet no longer follows, several of which came into play this week when Rovell tried to explain why taking someone’s photo and linking to their Twitter feed is better than simply retweeting them or quote retweeting them, a widely-used industry custom.

🚨 PEAK Rovell🚨 pic.twitter.com/ogZwqckoav

— Danny (@recordsANDradio) October 4, 2015

6. Always credit your source if you find content worth sharing. Think like a journalist when you’re passing along quality info.

Rovell took a photo from the feed of Hal Habib of the Palm Beach Post and rather than retweeting the image to his followers, he provided a “re-write” that he claims did more traffic for Habib than a retweet would have.

I keep wondering if these guys are performing at halftime with Katy Perry. pic.twitter.com/hcArKG6jPW

— Hal Habib (@gunnerhal) October 4, 2015

As you can see, Habib’s tweet received 5 retweets and 4 favorites. Rovell’s tweet got 73 retweets and 133 favorites. How, again, did stealing Habib’s photo and “crediting” him during a “re-write” benefit him?

Habib has 2,416 followers, and has gained 20 this week. From a journalistic standpoint, Rovell may claim he properly credited Habib, but the medium has changed, and quote retweeting now allows you to comment above a tweet while including the entire original, which is what Rovell should have done, rather than snagging the image for himself and giving a cursory tip of the hat he knew nobody would click.

Rovell routinely apes people’s photos off Instagram and “credits” them during his “re-write” without linking to their Twitter feeds or putting in an actual hyperlink to their IG account.

Scariest thing in London today? Dan Marino head (Instagram/SharkBaitLuke) pic.twitter.com/jT9M59TR1T

— Darren Rovell (@darrenrovell) October 4, 2015

That image, taken from Instagram, has 10 likes on IG. Rovell’s tweet has 59 retweets and 84 favorites. All in the name of journalism. And personal brand building.

You can make the case that at least there he’s giving credit to the photographer. Rovell also routinely posts images from public relations staffers for teams, brands and events without crediting the source. PR people don’t usually want the credit, but by Rovell omitting where he got the image he’s essentially taking image credit for himself. His feed is often valuable to his audience because he’s constantly aggregating images, but he should disclose that he is not taking many of the images he posts. Journalistically speaking.

In addition to routinely breaking Rule 6, Rovell broke four other rules after taking Habib’s photo.

48. When sharing a link, try to add a little flavor to it. Your followers want content from a person, not a robot.

Habib’s joke about Katy Perry was actually funnier than Rovell’s comment about dressing up like Dolphins. He took someone else’s tweet and removed the flavor.

56. Stop tweeting how much your Twitter account is valued at. The only thing your account is worth at that point is an unfollow.

To Rovell, Twitter is currency, and since he’s gained an astronomical number of followers since his Twitter rules were published, it’s almost understandable why he would go back on this rule as much as he does.

@mattyports @gunnerhal 23,000 more impressions for Hal's photo in 25 minutes. RT wouldn't do half that.

— Darren Rovell (@darrenrovell) October 4, 2015

Some years ago, a few companies tried to put a dollar valuation on our social media feeds, creating a ridiculous frenzy for growth like any of that “worth” would actually matter. Now, Twitter advertisers are more savvy, and thousands of deals are made for people with large followers to tweet advertisements to the masses. Value now is in impressions. Despite penning Rule 56, Rovell today wants everyone to appreciate his value.

81. Don’t plainly RT someone; add your touch to the tweet – even if it’s just a word or two.

82. Don’t always use Twitter’s “Retweet” button. If you find something worth retweeting, use “RT” & get the credit you deserve for finding it.

Rovell has decided in situations like this to no longer retweet at all, despite Twitter making it easier than ever to add your touch while still crediting the original tweet. Instead, Rovell takes what he wants. Because he’s all about engagement and value.

11. Don’t be tempted by the speed of Twitter. Take a breath before each tweet and ask, “If I was a follower, would I want to read this?” If not, delete it.

15. Quantity of tweets is fine as long as it’s quality. I average more than 40 tweets a day.

Most caloric single item in Yankee Stadium? Bottomless Popcorn Bucket pic.twitter.com/3HBD4JxA9I

— Darren Rovell (@darrenrovell) October 7, 2015

LIVE on #Periscope: Opening packs of 1987 Donruss Baseball https://t.co/gFuP7tLDQr

— Darren Rovell (@darrenrovell) October 5, 2015

20. Just because you are getting slammed doesn’t mean you should blame Twitter. Learn to absorb the hate and get a thicker skin, it’s useful in life.

Is it bad that I'm most concerned about my mancave flooding? #Sandy

— Darren Rovell (@darrenrovell) October 29, 2012

Rovell has developed a reputation since 2011 for attacking people on direct message that post about him before unfollowing them or blocking them. When I once made fun of Rovell’s famous “man cave” tweet (above) he sent me a barrage of direct messages before unfollowing me on Twitter so I couldn’t reply, then called my cell phone to yell at me more. At the end of the conversation he said he unfollowed me to protect himself from saying something he would regret, and he would refollow me when he cooled down. As of this post more than four years later, Rovell does not follow me on Twitter. Some months back, I finally wised up and returned the favor.

33. Check out your followers. If someone’s bio looks interesting, follow them.

72. If you have 200,000 followers and you follow no one, you aren’t getting the full Twitter experience. Twitter isn’t a megaphone, it’s a telephone.

75. Following athletes/celebrities is usually pointless. Twitter is about good tweets; not hearing an NBA star say, “What’s good, fellas?!” Make a list if you want to follow them, but don’t invite them into your timeline.

Rovell follows 1,760 people, which is a good number for someone of his Twitter stature, but it’s .06 percent of the number of people who follow him.

Many of the people Rovell follows are sports media or sports business types. Many of the people Rovell follows are athletes, too, including a runner with 156 followers, several members of the Northwestern University football team, two competitive eaters and the regular cast of athlete celebrities most media people follow these days, like Richard Sherman, Kevin Durant, Russell Wilson and… Noah Syndergaard.

Have athletes gotten better in the last five years at tweeting about their lives? Sure, some have. So either Rovell reconsidered that rule, or justifies following the likes of Allison Stokke or Genie Bouchard or Matthew Dellavedova or Brandon Weeden simply from a sports business perspective. That must be it.

39. Don’t tweet and drive. Unless you are very good at it.

I honestly don’t know if this rule has been broken or not, but I know it was stupid then, and seems even stupider now.

31. Know why people follow you. If you’re a foodie, don’t send 20 Florida Marlins tweets on a single night.

Somewhere along the way Rovell transformed himself into a Twitter foodie. He justifies the rampant posting of food as serving (pun) his audience, pointing out in the past that his food tweets trend as well or better than his sports business tweets.

Why not create a separate feed (pun) for the food tweets? Many people in the industry have a personal feed and a professional feed, and while Rovell has made the case that tweeting ballpark food falls under the umbrella of sports business, tweeting delicacies from the Texas state fair or shots of personal dinner plates should not.

Chicken Fried Bacon at the State Fair of Texas pic.twitter.com/N5GsQBAfUO

— Darren Rovell (@darrenrovell) October 5, 2015

(Rovell tweets so many food offerings from the State Fair of Texas—a follower of his—that it makes me wonder if they, or the bacon industry, are paying him for the tweets.)

Reading back on Rovell’s 100 rules now, you can see how he ran out of steam about halfway through and got redundant with his rules. He caught a second wind toward the end, however, with these two gems capping the point that if you’re going to go to all the trouble of creating a set of rules for the rest of us, you probably shouldn’t abandon them as often as he does.

95. If you experience Twitter writer’s block, just take a break. You don’t have a daily quota to meet, so there’s no need to force it. Your followers will be pleased with consistent, quality content.

97. Don’t tweet during important life occasions. Savor the moment; Twitter will be there for you when it’s all done.

Hopefully this is the end of the pumpkin "flavor" absurdity. Found this in my cabinet this morning pic.twitter.com/oC5yARm4qA

— Darren Rovell (@darrenrovell) October 5, 2015

Savor the moment next time, Darren. Also, that soap probably smells amazing.

Comments are closed.