Another year has passed by Baseball Hall of Fame voting without arguably the greatest hitter and pitcher of the last generation being elected to the sport’s most hallowed ground. Once again, Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens failed to register the needed 75 percent of votes from the Baseball Writers Association of America to be elected to Cooperstown because of their association with performance-enhancing drugs.

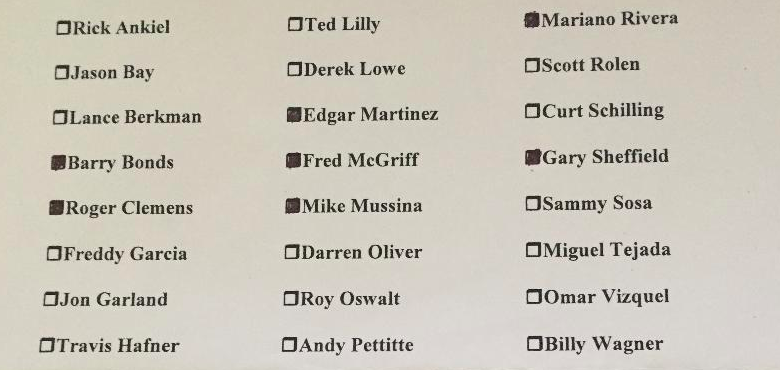

Four players were elected to Cooperstown this year: Mariano Rivera (who set a record by being unanimously selected), Roy Halladay, Mike Mussina, and Edgar Martinez. As far as the top vote-getters who didn’t make it, Curt Schilling led the list at 60.9 percent followed by Clemens at 59.5 percent and Bonds at 59.1 percent.

Both players are in their seventh year of eligibility with only three remaining. Bonds and Clemens have seen their support grow since gaining just 37 percent and 36 percent, respectively, in their first year on the ballot in 2013. However, that growth has diminished in recent years, rising just five percent since 2017. At this rate, it’s tough to see either man gaining enough support from holdouts to reach the 75 percent benchmark before they are removed from the ballot.

When it comes to Bonds and Clemens specifically, we may have a little more insight into why their Hall of Fame candidacies seem to be reaching a ceiling. It comes from the writers themselves and whether or not they are willing to reveal their ballot publicly. In short, writers who are willing to disclose their ballots are much more likely to vote for Bonds and Clemens than those who keep them private.

Ryan Thibodaux, who tracks Hall of Fame ballots, calculated the astonishing numbers. Voters were 25 percent more likely to vote for Bonds or Clemens if they made their votes public.

Initial Public/Private splits (with the caveat that we already have a handful more post-announcement ballots to add):

Bonds: 70.1% | 45.5%

Clemens: 70.5% | 46.1%

Halladay: 92.7% | 76.4%

Mussina: 81.6% | 70.7%

Schilling: 70.1% | 49.7%

Vizquel: 38.0% | 48.7%

Walker: 65.8% | 40.8%— Ryan Thibodaux (@NotMrTibbs) January 23, 2019

In case you’re wondering whether this is a new phenomenon, the same has been true in recent years as well.

https://twitter.com/lindseyadler/status/956183207787065344

There are a couple of theories that one could infer from this data.

Vote trackers are a relatively new idea when it comes to the Baseball Hall of Fame. But given the scrutiny that can come with revealing one’s ballot, it’s not a practice that all voters would want to embrace. A voter opens themselves up to a torrent of debate and criticism if the baseball populous would disagree with their choice. We’ve already seen that impact. Mariano Rivera was a unanimous selection even though one Boston writer originally stated he was not going to vote for him. An avalanche of criticism apparently changed his mind because he did end up voting for Rivera.

Given that the majority of public voters are giving Bonds and Clemens the thumbs up, voters who are in the minority position may not want to put themselves out there and risk the backlash. If you publish a ballot that doesn’t have Bonds or Clemens on it, you can expect your social media mentions and e-mail inboxes to be full of people telling you how sanctimonious and self-righteous you are for doing so. It makes sense that voters who may have more of a traditionalist slant, who want to protect the Hall of Fame from anyone remotely associated with the steroid era, should want to keep their ballot private. It’s interesting that the only name to receive more private votes than public ones is Omar Vizquel, a player whose resume might appeal more to traditionalists and those looking to make a statement against the steroid era.

Are Bonds’ and Clemens’ Hall of Fame chances doomed? Not necessarily. Jeff Bagwell saw his percentage jump from 55 percent to 86 percent in just two years. But the data shows that there is indeed a divide in the Baseball Hall of Fame electorate when it comes to the two most controversial names on the ballot. And it’s hard to imagine bridging that gap in the next few years.