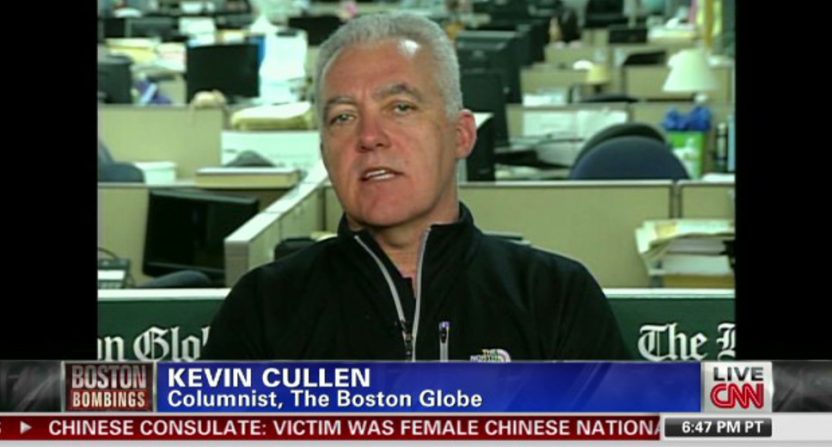

Back in April, Boston Globe columnist Kevin Cullen’s writing on the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings came under scrutiny, with WEEI’s Kirk Minihane noting that both a five-year-anniversary piece and a piece Cullen wrote the day after the bombings appeared to have him on the scene when the explosions happened (which he admitted he wasn’t in later interviews), and appeared to contain other erroneous, unverifiable or fabricated details.

The Globe placed Cullen on paid administrative leave while conducting an investigation into those pieces and his media appearances at the time) (led by retired AP executive editor Kathleen Carroll and Boston University dean of the College of Communication Thomas Fiedler), and a separate simultaneous investigation into his other work (led by Globe editors Scott Allen and Brendan McCarthy and former Globe staff writer Joseph Kahn).

Those investigations have now wrapped up, with the first one finding numerous severe problems with Cullen’s work around the bombings and media appearances around then, but the second finding only minor errors in his other work. However, the second investigation did also conclude that Cullen’s columns sometimes used “journalistic tactics that unnecessarily raise questions about his accuracy,” which could “open the door to providing seriously misleading information to the public.” The paper has announced that Cullen will receive a three-month suspension without pay as a result of the two investigations. Here are the key parts from the Globe‘s statement:

The first review revealed significant problems, particularly a series of radio appearances by Mr. Cullen early in the morning of April 16, 2013, that, in the words of Ms. Carroll and Mr. Fiedler, “raise the concern of fabrication.” Specifically, the review found that Mr. Cullen details “scenes in which he was centrally involved but, to the best of our knowledge, didn’t occur.” Mr. Cullen described conversations he had with members of the Boston Fire Department that don’t appear to have happened. When asked about these radio appearances in two meetings in April and May, Mr. Cullen failed to provide an adequate explanation. In addition, Mr. Cullen appeared on a journalism panel in August 2013, broadcast on C-SPAN, in which he offered details of a scene on the night of the bombings that Ms. Carroll and Mr. Fielder conclude was a “complete fabrication.”

The problematic assertions made by Mr. Cullen in broadcast interviews never appeared in the pages of The Boston Globe, which explains at least in part why editors did not learn about them until five years later, when they were publicly raised. But Mr. Cullen did make a key mistake in his first-day column that was never corrected – a violation of Boston Globe standards and practices. This was an editorial breakdown that should have been corrected by both Mr. Cullen and his editor, Jennifer Peter, when they became aware of the mistake on April 16.

…Our review leads us to a conclusion that Mr. Cullen damaged his credibility. These were serious violations for any journalist and for the Globe, which relies on its journalists to adhere to the same high standards of ethics and accuracy when appearing on other platforms.

Our review also leads us to believe that Mr. Cullen did not commit irrevocable damage. His long Globe career has been an exceptional one, from his start as a crime reporter to his role helping to uncover the protection Whitey Bulger received from the FBI, to his key contributions to Spotlight’s work revealing the Catholic Church pedophile scandal. He has written hundreds of highly read and often impactful columns about people from every walk of life without this organization receiving any complaints about the authenticity of his work. He has also acknowledged his failures and the issues they have created. “I own what I did,” Mr. Cullen said in a recent email, adding, “I accept responsibility for these shortcomings and I’m sorry that it has allowed some to attack the Globe itself.”

A three-month suspension without pay is quite significant, but many also may not see it as enough, especially when the investigation concluded that a scene Cullen described on a journalism panel was “a complete fabrication” and that other scenes he described “to the best of our knowledge, didn’t occur.” Fabrication is a huge problem in journalism and has led to some of the profession’s biggest scandals, including those around Stephen Glass and Jayson Blair, and both of those people haven’t worked in the field in any notable sense since. Cullen’s actions aren’t necessarily on the scale of to what Glass or Blair did, as fabrication and/or plagiarism issues popped up in hundreds of pieces they did rather than in a couple of pieces and in outside media appearances (and this is why the second investigation of Cullen’s other work was done; if further fabrication had popped up there, the punishment likely would have been more severe), but they still raise the question of if readers will be able to trust him.

The latest

In that case, Cullen not only misidentified the first responder in question, he relayed a story that no one has been able to substantiate (with one firefighter calling it “crazy”). And he did so while saying he got it directly from the firefighter in question. (Although he now says he got it from “other firefighters who would have known.”) And while the aftermath of an event like that is obviously chaotic, getting something so dramatically wrong (and being so emphatically certain about it) is something that raises long-term questions for Cullen’s credibility.

Perhaps the Globe decided Cullen deserved another chance given his past work, and believed his explanation here that these particular errors came from erroneously relaying what he heard rather than pure fabrication. But that’s problematic, with even with their outside reviewers finding that at least one scene he described was “a complete fabrication.” And keeping him around after this is at the least a controversial decision. We’ll see what happens when he returns to the pages of the Globe, but readers may approach his columns with a whole lot more skepticism after this.

[Deadspin; screencap from a 2013 Cullen interview on CNN]