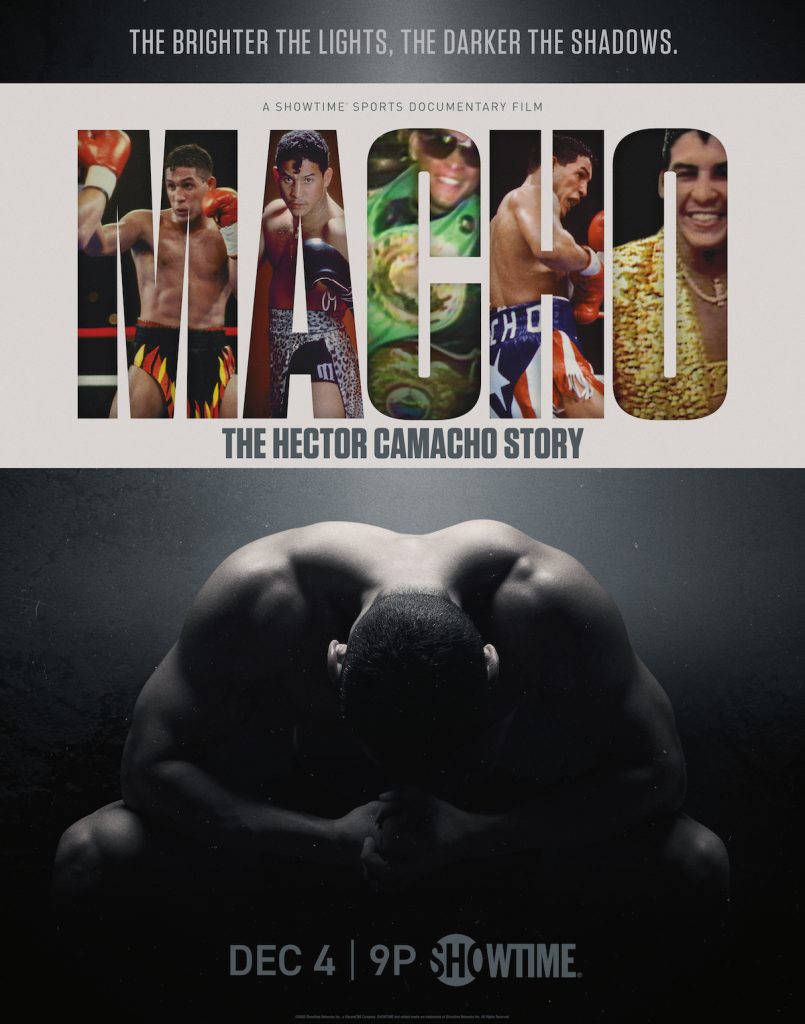

“I liked Batman, I loved Superman, the Lone Ranger, Zorro… you put all those superheroes together, there’s nobody like the Macho Man.”

Boxing fans who grew up watching the sport during the 1980s should love the Showtime documentary, Macho: The Hector Comacho Story. Camacho may have come off as boastful when talking about himself and his talents. But he was absolutely right in saying that there was no one like him in boxing during his prime and we’ll probably never see anything like him again.

The documentary by Eric Drath (30 For 30: “No Más”) is an outstanding reminder of how eventful boxing was during that era and how many stars fans were able to watch in the ring. And the biggest stars weren’t in the heavyweight division either. Sugar Ray Leonard, Roberto Duran, Marvin Hagler, Thomas Hearns, Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini, and several others provided fans and networks so many exciting boxers to follow.

Boxing has been greatly diminished in popular sports and mainstream culture, so some fans might be surprised to see a time when CBS televised major fights and was a showcase for the sport. The network also made efforts to attach itself to up-and-coming stars like Camacho who captured the attention of viewers and broadcasters like Tim Ryan, one of the many people interviewed in the documentary.

After a January 1985 fight against Louie Burke, Camacho breaks down during a post-fight interview with Ryan. He begins crying and puts his head on Ryan’s shoulder because of the adversity created by his drug use and increasing popularity. As conversations with family, friends, and associates in Camacho’s life explain during the film, these are issues that afflict the boxer throughout his life.

Macho chronicles Camacho’s career from the beginning, growing up in Spanish Harlem and taking up boxing to stay away from the drugs and violence prevalent in the area at the time. He achieved success and notoriety as a Golden Gloves competitor, developing the skills — quick feet, fast hands, constant movement — that would make him a formidable professional fighter.

Drath interviews former trainers Robert Lee Velez and Billy Giles, along with analysts including Teddy Atlas, to explain just what made Camacho so good. His jab was that much quicker because he wouldn’t turn his fist as most fighters do. Camacho would just use his elbow and shoulder to fire quickly at his adversary. One of his signature moves was to dart to his right, getting his opponent to shift his weight and leave him open for a lethal left-handed uppercut.

As Camacho’s profile grew, he knew the “Little Man” nickname he had growing up wasn’t enough. So he took the nickname “Macho,” playing off his last name and his persona made him one of the most popular stars in the sport.

Soon thereafter, Camacho became famous for the garish outfits he wore to the ring, many of which Drath shows in montage footage. He could be a Roman soldier, a Native American warrior, a sci-fi superhero, or a glam rock star before a fight. How many fighters wore a brightly colored, sequin-studded robe, only to shrug that off his shoulder to reveal another elaborate robe underneath?

Several of those costumes were designed by the boxer himself with markers on paper. One of the more entertaining interviews in the film features Camacho showing cutouts of his ideas to the camera, almost like a schoolkid drawing superheroes and showing them to his parents.

Camacho’s story eventually follows a familiar path in which he falls from the heights of stardom and his skills erode as the physical punishment of boxing and age take their toll. But his self-destructive habits, particularly his drug addiction, are the most difficult to overcome. In a heartbreaking scene toward the end of the film, Camacho’s lifelong friend explains that the boxer squandered a big late-career payday because he didn’t want to put in the effort to train. He just wanted to get high.

The final quarter of the documentary takes sort of a turn into true crime while recapping Camacho being murdered in a drive-by shooting in his native Bayamón, Puerto Rico. (Camacho had fled to Puerto Rico to escape felony child abuse charges.) Drath goes back to the scene of the crime, talking to friends Camacho hung out with, along with police officers and FBI agents who worked on the case.

But as the filmmaker discovers, very few murders are solved in Puerto Rico and Camacho’s murder is no exception. Yet the investigation is still ongoing with new FBI agents on the case. Very few documentaries have sequels, but Drath might have one on his hands if law enforcement is able to zero in on who shot Camacho.

Many sports documentaries suffer from filmmakers not being able to interview every key figure in a story. But Drath finds everyone he needs to tell The Hector Camacho Story. His passion for the subject and persistence in pursuing every angle is apparent in the work shown here.

Drath is also surely grateful that cameras seemed to follow Camacho everywhere he went, whether it was his associates who tried to chronicle everything or TV producers were always eager for content. There is an abundance of footage shown in this film, helping put together an outstanding documentary.

Macho: The Hector Camacho Story premieres on Showtime Friday, Dec. 4 at 9 p.m. ET. The documentary can also be streamed by subscribers on the Showtime website and app or viewed on-demand.