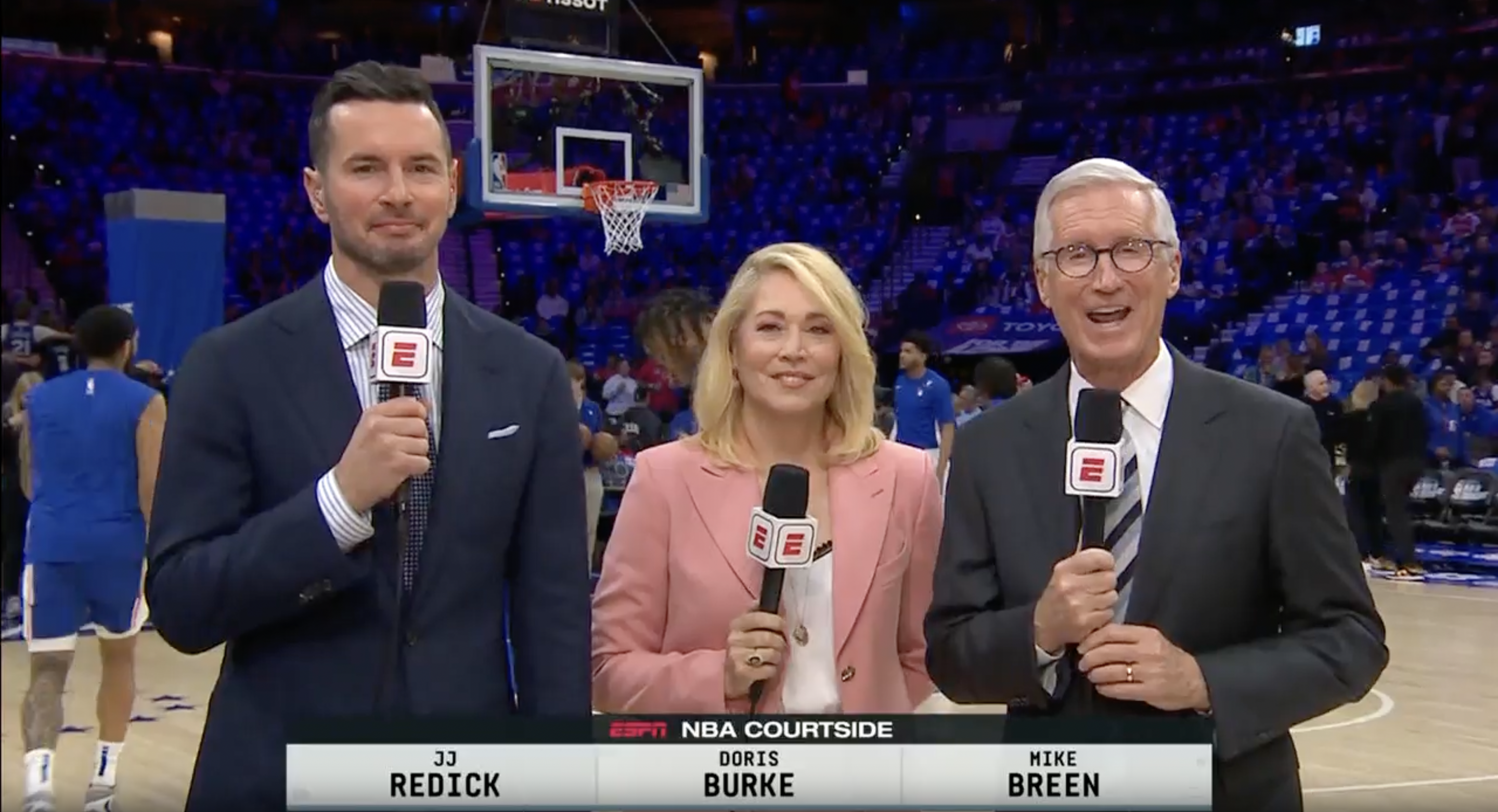

Opening up branded sports bars has long been a thing, but that hasn’t always worked out, with some less-than-stellar success stories including the ESPN Zone (once a chain, but most of its locations (including the Baltimore one seen above) closed in 2010, and it now has just one soon-to-close sports bar near Disneyland in Anaheim and two related ones at Disney World in Florida) to the Fox Sports Grill (which used to have a bunch of locations, many of which closed or rebranded, and now appears down to one in San Diego).

Players, coaches and teams are still doing it, though, as with Gretzky’s, Ditka’s, or many others, or the airport bars opened in partnership with the Dallas Cowboys and Vancouver Canucks (among others). And Barstool Sports looks to be the next media outlet contemplating the move.

Jay Caspian Kang’s long New York Times Magazine feature on Barstool in the wake of the cancellation of their ESPN deal is an excellent look at the company overall, but the biggest news out of it may be the discussion of Barstool debating opening a chain of sports bars. Here it is, part of a larger paragraph on their branding and partnerships.

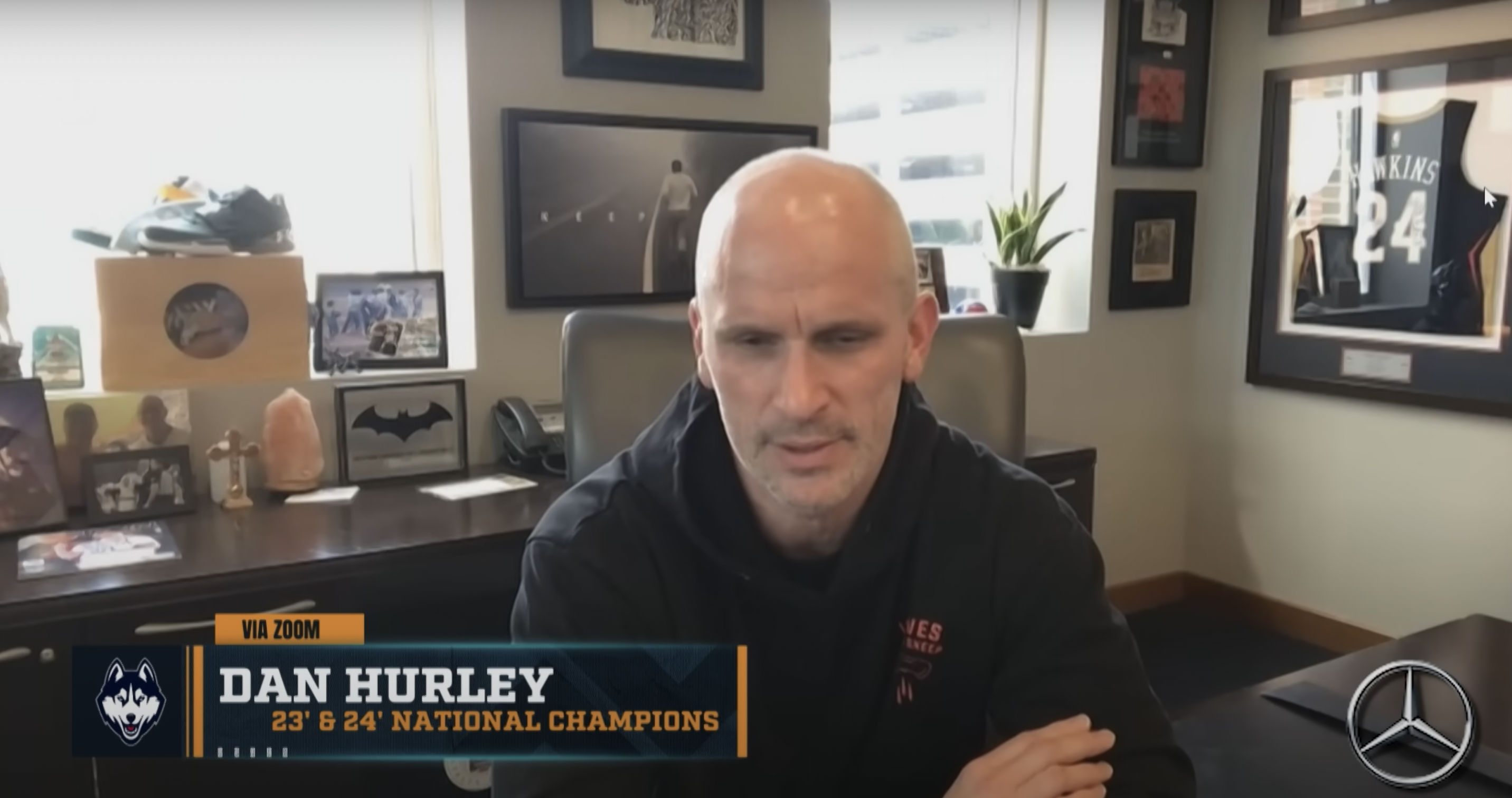

The Barstool acquisition was engineered by the president of Chernin Digital, Mike Kerns. “When I got access to Barstool’s Google analytics, I knew this was something different,” he told me. “They had something like 20 percent of their visitors coming back about 20 times a day. I’ve been in this business for two decades, and all their numbers bucked the usual trends.” Portnoy kept full editorial control; Chernin’s bet was that it could serve cheap content to his loyal fan base, which would then pay for things like T-shirts, events and premium content. The brand would be scaled up into something that could be sold to advertisers, big media partners and even sports leagues. Every Barstool executive I spoke to mentioned the possibility of opening branded sports bars across the country; all of them talked about partnerships with networks. Since its acquisition, Barstool has released a raft of popular podcasts — including “Pardon My Take,” which, with downloads running up to one million per episode, is one of the biggest sports podcasts in the country. It has partnered with Facebook on a roving pregame college-football show (since canceled) and produced a widely watched baseball show that regularly features former major-league players.

Widespread chains of licensed sports bars didn’t really pan out for ESPN or Fox (although some individual locations appear to have done okay, and things like the ESPN Zone also have branding benefits for Disney), but there might be more merit to this idea for Barstool. For one thing, Barstool has a ton of actual fans; people watch ESPN or Fox for games, and sometimes for studio programming, and might describe themselves as fans of particular analysts or shows, but it’s rarer to see fans of those giant corporate brands, while Barstool (although corporate in at least one sense following the Chernin acquisition) has a lot of people who seem not only loyal to it as a company, but eager to buy Barstool-branded merchandise. And in some ways, that makes them more similar to the teams opening up branded bars than to the media outlets that have tried it; Barstool has actual fans.

The latest

Meanwhile, ESPN and Fox’s sports connections are mainly “the channel you flip on to watch the game” (or maybe some studio shows, but judging by the ratings, maybe not so much). And even channels that show games have issues as a sports bar; yes, the ESPN Zone locations will show games on Fox or CBS, but there’s a branding dissonance there. Barstool’s a non-rightsholder that’s just about sports discussion, so that isn’t the case with them. And they’re certainly not afraid of connections to alcohol. Consider these lines from Caspian Kang’s story on Barstool’s branding:

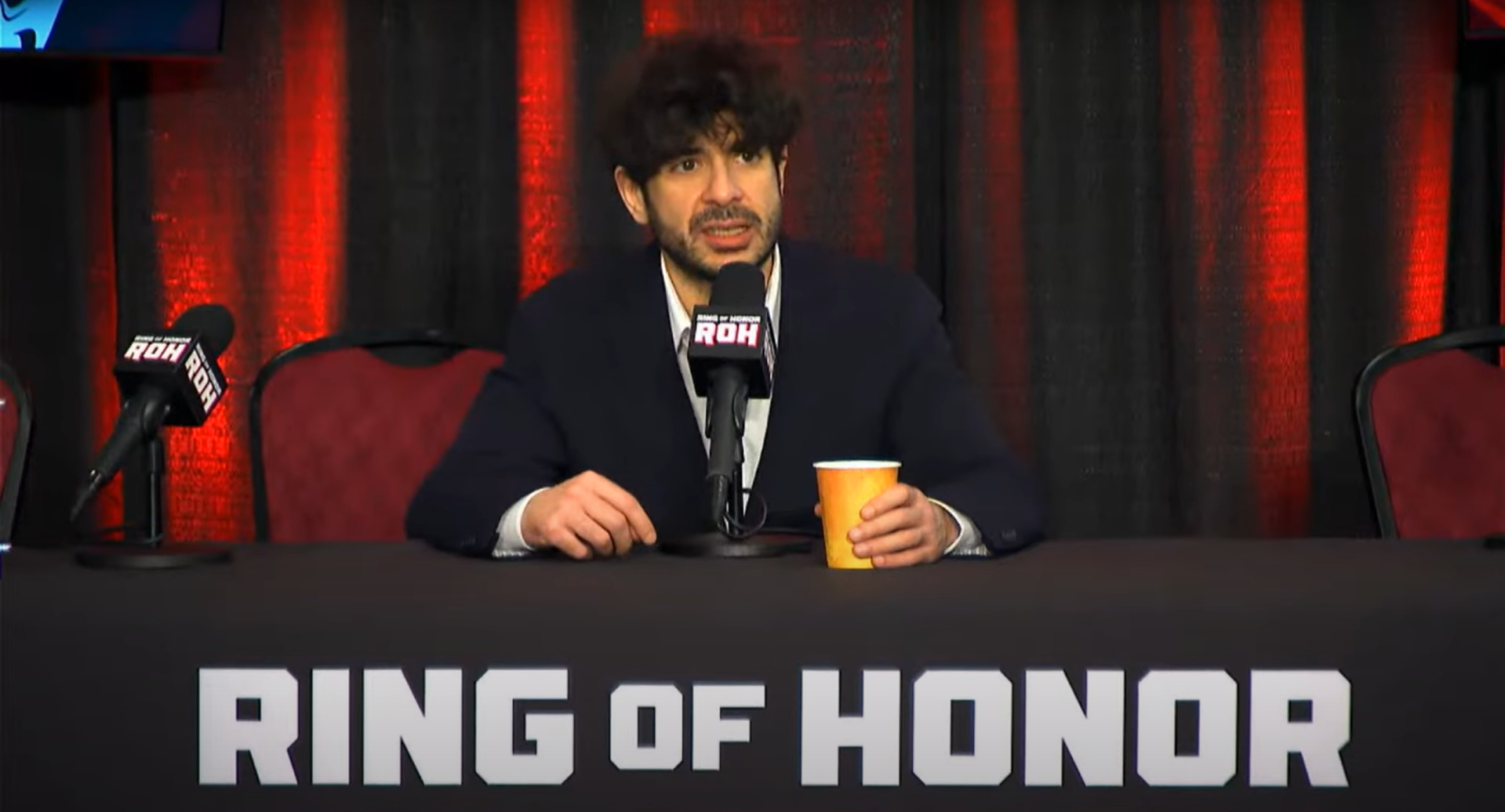

Portnoy’s talent was for gathering feedback from readers and advertisers and tweaking his product accordingly: “We could pivot really easily,” he told me, “and chase money.” The first breakthrough came when a local photographer told Portnoy he should start putting photos of area women on the tabloid’s covers — and offered to take the pictures himself. (A version of this idea still exists on the website, under the title “Local Smokeshow of the Day.”) Around the same time, Portnoy noticed that readers seemed to respond more to stories about drinking, women and gambling than day-to-day sports news. He sold ads to bars and breweries and catered more and more to a certain archetypal Boston bro — the type who puts on a collared shirt to get blackout drunk every weekend while ruefully cheering on the Red Sox. His writing voice fell into a distinct rhythm, half-cocked and prone to fits of anger. When he finally mustered up a web version of Barstool, it looked like a relic from the 1990s and often crashed, but he called such inconveniences “the Barstool difference” — a sign, he maintained, of true authenticity.

…[In 2010], he hired a local white rapper named Sammy Adams and set up a tour of New England colleges. “When we showed up on the campuses, they had our signs on their dorms, people were rushing after our bus,” he told me. “That was the first time I really thought this might be bigger than I anticipated.”

The following year, he started a nationwide party tour called “Barstool Blackout.” The college students who attended danced under blacklights and occasionally — the obvious implication — drank until they blacked out.

So, all of that seems to fit with bars in a way ESPN and Fox couldn’t. But will it actually work? For this to pay off, either new Barstool bars would have to do well competing against local non-licensed bars, or Barstool would have to be able to convince existing local bars to pay them for licensing rights. Both of those scenarios could work, especially if Barstool fans adopted the idea in droves, and they could pay off, especially if the end product is liked. And maybe there are some ways to synergize this with Barstool content, perhaps having live podcasts from the bars or having Barstool personalities as special guests on certain days.

However, there’s backlash potential. On one level, this could be seen as Barstool getting “too corporate” and losing their vaunted authenticity. Beyond that, there’s the chance of the experience at the actual bars not being great, which might even turn people off Barstool’s content. That’s to say nothing of the Barstool critics who might actively avoid something labeled with their name, too, or the female customers who might opt to not visit something named after a site with a “Saturdays Are For The Boys” slogan (to say nothing of their other controversies). And running successful bars is a very different business from publishing media content, as Disney showed by shutting down five of their ESPN Zones in 2010. (They blamed the economic slump, but there was a bit more to it.)

We’ll see if Barstool actually pursues this idea, and if so, how it turns out for them.