For decades, the NFL played two-hand touch with independent journalists. Under new communications chief Joe Lockhart, though, the league is putting The New York Times through the Oklahoma drill.

Last week, the Times ran a feature piece that rehashed the well-documented sins of the Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee, reported the committee’s studies relied on incomplete data and explored the league’s legal and business relationships to “Big Tobacco”—insinuating, if not quite reporting, the NFL modeled its efforts to minimize their risk after the tobacco industry’s denial of health risks and avoidance of lawsuits.

This is far from the first time a major media organization delved into the NFL’s head-trauma sins. In 2013, ESPN reporters Mark Fainaru-Wada and Steve Fainaru wrote the book “League of Denial,” and collaborated with PBS’s Frontline to produce a companion documentary film. Last year Sony released Concussion, featuring Will Smith as the pathologist whose work, career and reputation was smeared by NFL doctors and lawyers.

The NFL’s responses followed a long-familiar template: Bland official statements like the one longtime NFL PR chief Greg Aiello gave Time, Sports Illustrated‘s The MMQB and other outlets writing about the Sony movie’s impact: “We welcome any conversation about player health and safety. Broader and deeper awareness of these issues will positively impact all athletes.”

The NFL didn’t welcome the Times‘ report.

Brian McCarthy, who’s taken over Aiello’s role as the league’s day-to-day spokesman, dropped a 1,052-word official response to the story just hours after it went live—with an even weightier rebuttal to come:

here’s our statement on the NY Times story. We will have an even more detailed response this afternoon https://t.co/fq2AbDsnBu

— Brian McCarthy (@NFLprguy) March 24, 2016

Sure enough, Lockhart penned an aggressive, 2,520-word point-by-point rebuttal that used the phrase “The Facts Prove Otherwise” an awful lot. Lockhart didn’t just deny the claims made by the Times‘ reporters. He went to great lengths to accuse the Times of publishing “false innuendo and sheer speculation” that fit a “predetermined narrative,” as opposed to parroting the information the league fed them.

The Times responded with its own point-by-point rebuttal of the NFL’s point-by-point rebuttal. In a moment sports media wonks can only wish Fire Joe Morgan was still around for, the richest sports league in the world and America’s newspaper of record Fisked each other.

Ultimately, it was much ado about not very much: Lockhart conceded the league’s published medical studies “should have been clearer” about the limitations of their data sets, most of the rest of it was a pointless back-and-forth about the Times‘ reporting. If that’s where it stopped, this wouldn’t signal a sea change in the way the NFL handles its messaging. But the league was just getting started.

Lockhart, a former White House press secretary during the Clinton era and longtime D.C. communications consultant, brings a completely different way of handling information to the NFL.

Last winter, the league seemed content to cross their fingers and hope a major motion picture dramatizing these events wouldn’t hit them too hard. This spring the league won’t cede an inch to a newspaper story that doesn’t cover much new ground.

In a stunning move, the NFL ran a huge round of ads on the Times‘ site highlighting all the work they’ve done for player safety, per The Wall Street Journal, including on the article page itself. They also did major buys on Twitter and Facebook, as well as leverage their in-house media operations.

As McCarthy told HuffPo, it’s all part of a “multiplatform strategy” to discredit the story and promote their own messaging. The message they mean to send is that the NFL takes player safety very seriously, but another message came through loud and clear to everyone who tries to dig up dirt on the NFL: buckle your chinstrap.

The media-cycle flames died down over the weekend, as they tend to do, and the issue was all but forgotten—until today, POLITICO obtained a letter sent to the Times by the NFL’s attorneys, demanding a retraction of the story. McCarthy then threw a can of gasoline onto the flames with this Tweet:

just asking: why is it ok for NY Times to use consultants/lawyers who repped tobacco companies & have board members who sit on their boards? — Brian McCarthy (@NFLprguy) March 29, 2016

There are two big takeaways from this.

One, the Times relied on facts most Americans don’t think about to tell what seemed like a compelling story: There are only so many billionaires in America, and only so many high-powered corporate liability attorneys in New York. Pick a U.S. industry with black marks on its record, and there’s an NFL owner with strong ties to it. Just try finding lawyers capable of helping multi-billion-dollar organizations avoid multi-million-dollar lawsuits, but who haven’t ever worked for a client that did bad stuff.

What the Times did was suggestively nudge a few facts into the proximity of a few others, and let readers make the leap to the desired conclusion. Sports editor Jason Stallman told POLITICO he sees “nothing to retract,” which makes sense because there wasn’t anything reported.

The other: The league office is playing a completely different PR game this season.

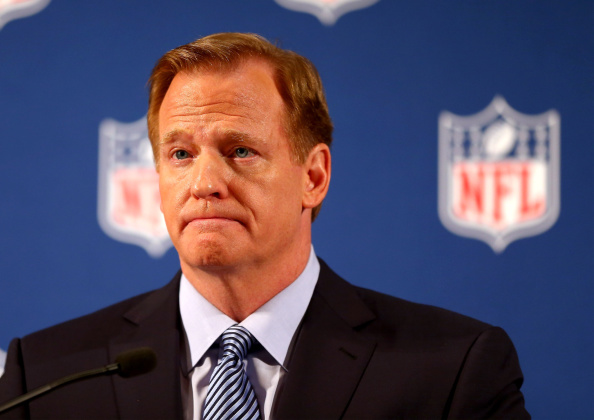

Pro Football Talk called Lockhart’s hiring “some insulation for Roger Goodell,” but that might be true in more than one way. Yes, a D.C. communications maven will be able to help Goodell “get it right” the first time more often. But more importantly, Lockhart can deploy his savvy—and McCarthy, whose approachable Twitter bio hasn’t changed since he joined the site as a junior PR staffer—to sell the league’s messaging without getting Goodell’s hands dirty.

This might be the new normal for the NFL. Rather than ignoring bad stories until they become un-ignorable, then issuing a simple statement, with Goodell going on camera as the break-glass-in-case-of-fire option, Lockhart and McCarthy can aggressively, relentlessly respond to emergencies of all sizes in real time.

If this is how the NFL reacts to reporters re-investigating a past the NFL has already put behind them, though, how will they handle reporters looking into the NFL’s current research and safety efforts? This seems like a warning to the “Frontline”s and “Outside the Lines”es of the world (not to mention humble columnists like yours truly) to toe the line or risk incurring the league’s weeklong, multiplatform wrath.

Only time will tell if this new fight-fire-with-fire approach will put out more fires than it starts.