The NCAA men’s basketball Final Four and championship game ratings took steep year-over-year downturns overall (partly thanks to cable, partly thanks to last year’s sky-high numbers), but there was a very interesting split in the numbers. Turner’s decision to show alternate Team Stream feeds on TNT and truTV in addition to the main TBS broadcast is similar in concept (although quite different in content and tone) to what ESPN’s done with the college football national championship Megacast, but those Team Streams (which started in 2014, a year before the Megacast) have proven far more popular than ESPN’s alternate feeds. Is that about Turner’s homer-friendly Team Streams being more popular content than the alternate ESPN feeds, or about confusion from viewers, or is it some of both?

First, let’s discuss just how different the numbers are. The 2016 Megacast added a total of 512,000 viewers across ESPN2, ESPN News, ESPNU and ESPN Deportes, while the main game broadcast drew 25,667,000. Thus, all four Megacast channels combined drew less than two per cent of the main game’s audience. By contrast, the late Final Four game Saturday (North Carolina-Syracuse) drew 10,152,000 million viewers to TBS, 2,158,000 to TNT’s North Carolina Team Stream and about 600,000 to truTV’s Syracuse Team Stream. The TNT broadcast alone hit 21.3 per cent of the base game’s audience, while the combination of both Team Streams boosts them to 27.2 per cent. Sports Business Journal‘s John Ourand’s numbers for Monday’s championship game continue that trend, with TBS’ main broadcast pulling in 13.853 million, TNT’s North Carolina Team Stream landing 3.127 million (22.6 per cent) and truTV’s Villanova Team Stream reaching 772,000 (5.6 per cent on its own, 28.2 per cent combined with the TNT broadcast).

This isn’t a one-year trend, as the story was similar during the 2015 Megacast and Team Streams. ESPN’s 2015 Megacast had around 700,000 viewers across its channels compared to around 33,400,000 for the main broadcast, pulling in just over two per cent of the main broadcast’s audience. By contrast, last year’s Wisconsin-Kentucky Final Four game saw 16.796 million viewers on TBS, 4.501 million on the TNT Kentucky Team Stream (26.8 per cent) and 1.329 million on the truTV Wisconsin Team Stream (7.9 per cent alone, 34.7 per cent combined), and Duke – Michigan State pulled in 11.138 million viewers on TBS, 3.415 million on TNT’s Duke Team Stream (30.7 per cent) and 754,000 on truTV’s Michigan State Team Stream (6.8 per cent alone, 37.5 per cent combined). So, these feeds are drawing huge numbers compared to ESPN’s alternate programming. The big question is why.

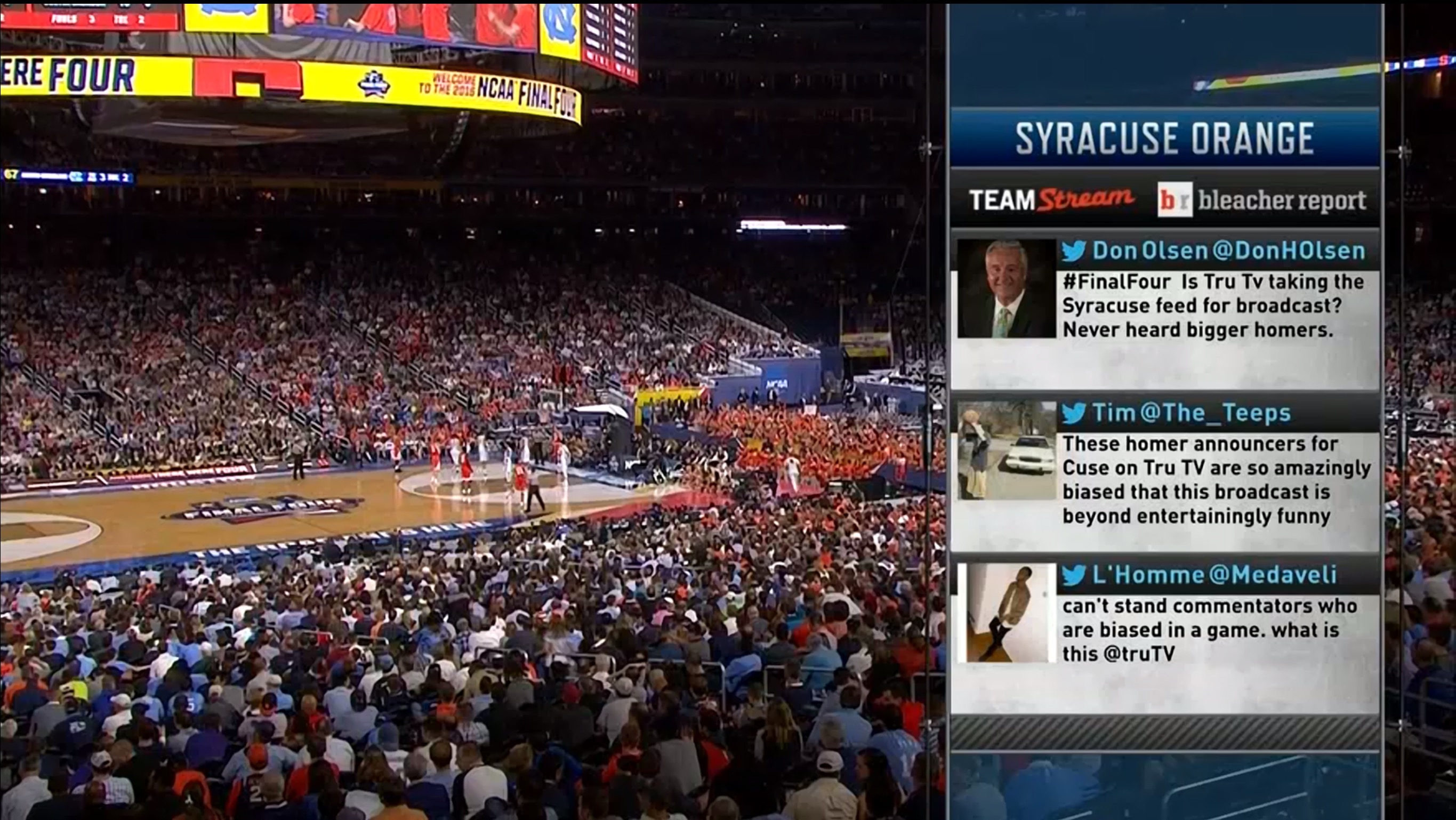

From this corner, it seems the answer is probably partly confusion and partly content. Confusion still exists despite the many promotional attempts to explain the TeamStream concept, with even Charles Barkley’s friends texting him about announcer bias. Part of the reason for the confusion is that these broadcasts are much more similar to a traditional broadcast than ESPN’s alternates. It’s easy to tell that a coaches’ film room or a group of ESPN personalities watching the game is something different, but the Team Streams are mostly a typical game broadcast, just with team-specific commentary. However, Turner did do a lot on-screen to illustrate that this was something different, even showing shots of the announcers’ reactions and Twitter complaints about the biased announcing, and there’s been plenty of media coverage of the concept and popular discussion of the concept over its three years of existence. So, while confusion explains some of this, it doesn’t explain the whole thing.

There appears to be a solid market out there for announcing that favors one team, which we’re often seeing on regional sports broadcasts. The balance of homerism and objectivity is different from broadcaster to broadcaster, of course, but many of the most popular local broadcasts do trend towards significant homerism. Thus, it makes some sense to do this concept for a national broadcast, especially when you have the channel space to do so. (It’s notable that ESPN did some of this on the Megacast too, but offered one homer broadcast for both sides on ESPNU, with an analyst from each team.) While some of the audience for Final Four and national championship games is neutral and wants a neutral broadcast, and while even some fans of the teams involved want a traditional neutral broadcast, there appear to be plenty of people who do want content focused towards their team. Beyond that, too, the Team Streams present a full-screen focus on the game in a way most of ESPN’s Megacast feeds didn’t, instead often showing coaches or personalities in a split-screen setup, so they might be an easier watch for some. The big numbers for the Team Streams aren’t all confused viewers.

Does this mean that the Team Stream is more successful than the Megacast? Not necessarily, as there are benefits to both ideas. Spreading out the audience more the way the Team Streams do means that the alternate channels can command higher ad prices, but it dilutes the audience (and thus, the ad prices) for the main broadcast in a way the Megacast hasn’t. Without seeing the ad numbers and the additional production costs, we can’t conclude which approach is better from a bottom-line perspective, but you can make a case for either. The other downside of the Team Stream is that it seems to be more of a pie-division than the Megacast; rabid fans are going to watch the neutral broadcast without a team stream, but vastly-different features like a coaches’ film room or ESPN personalities watching and discussing the game might pull in some new viewers who wouldn’t be devoted to the standard broadcast. Both of these approaches have their ups and downs, and both of them seem to have worked out for the companies doing them so far. It is fascinating to see how different the audience breakdown is for Team Streams versus the Megacast, though.

Comments are closed.