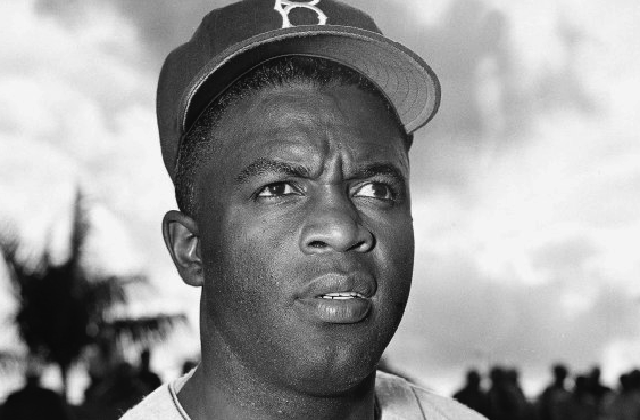

After establishing how proud Jackie Robinson was of his race, how important equality was to him, and how hard he fought against prejudice and persecution, part one of Ken Burns’ Jackie Robinson documentary recounts his path to becoming the first black man to play in the major leagues.

Much of that story will ring familiar to those who have followed and studied Robinson’s career, and learned of his place in baseball and cultural history. But Burns (with Sarah Burns and David McMahon) brings the mythology to life, adding depth and humanity — particularly through Robinson’s own words, voiced by Jamie Foxx — to what many may have previously gleaned through text, black-and-white photos and the occasional classic film clip.

Burns’ greatest asset in giving Robinson life in his film is the presence of his wife, Rachel. What better way to make the legend come alive than for her to talk about her husband, to explain he was a man with flaws and struggles, to demonstrate her love and pride for Jackie with every word she speaks. Robinson has no better storyteller than the woman who lived through it all right there with him.

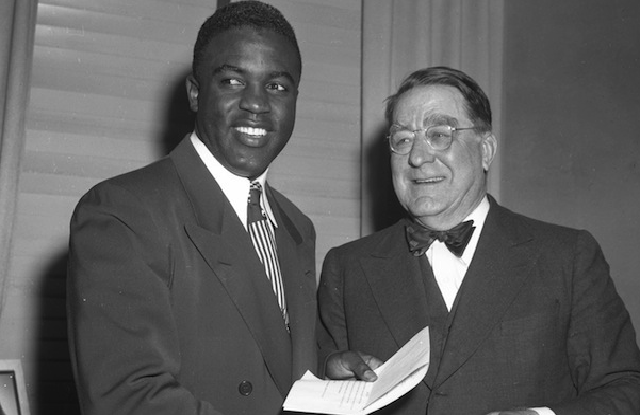

For all of the defiance that was a central part of Robinson’s personality, Brooklyn Dodgers president and general manager Branch Rickey impressed upon him that it was vital to endure the insults, mistreatment and ignorance he would face.

Robinson had to show he could be the better man, to not confirm any of the fears and misconceptions white fans, players, coaches and executives held toward the idea of black players entering the major leagues. He faced racism on his own team, from players who were born and raised in the South, who not only had their racist perceptions, but had to answer questions at home about playing with a black man. Rickey held firm, either trading away those who said they’d refused to play with Robinson or ignoring their protests.

Opposing players talked about going on strike and refusing to play against the Dodgers if Robinson was in the lineup. But those threats never materialized. No one sat out a game, no games were forfeited because a team wouldn’t play. Of course, that’s not to say that Robinson didn’t face intense hatred and scrutiny on the field. Pitchers threw at his head. Baserunners stepped on him with their spikes. Managers and players frequently yelled insults at him from the dugout.

Though Robinson weathered the repugnant treatment, it did take a physical, mental and emotional toll on him. And his play suffered at times because of it. Yet despite his worries about being benched, Rickey stuck by Robinson, not giving up on his noble experiment. Robinson stayed in the lineup and players that may have supplanted him were traded away. It was a demonstration of faith that Robinson soon justified, emboldened by the knowledge that Rickey wasn’t going to abandon their objective when things became difficult.

** In Part 1, Ken Burns’ Jackie Robinson film defines the man, not the baseball icon

But Robinson didn’t just change baseball by knocking down racial barriers and leading the way toward the sport’s integration. He also changed the culture of how the game was played. As Negro Leagues legend Buck O’Neil explains, “Jackie took black baseball to the major leagues.”

Previously, the game was played base-to-base, with runners moving along following hits. But in the Negro Leagues, players brought more action and created offense through other means. Drawing walks and getting on base led to stolen bases (even stealing home plate), sacrifice bunts, and scoring runs without getting hits. There was no waiting for the next hit. “When you combined speed with power,” historian John Thorn said, “you had the beginning of the modern game.”

Footage of Robinson (some of it in color) getting base hits, bunting for infield singles, taking huge leads off first base, and running around the bases with speed, quickness and agility demonstrates what O’Neil and Thorn describe. To contemporary fans, the style of play might look familiar (though the baserunning seems more energetic). These days, we praise disrupters in the business and technology worlds. Baseball was changing, and Robinson was leading the revolution.

Of course, Robinson’s breakthrough and subsequent success was also changing baseball off the field and in the stands. Many more black people were attending games, sometimes filling up half the ballpark and creating crowds of thousands outside. Robinson and the Dodgers coming to town was an event. Owners worried that integrating black players into baseball would hurt attendance by scaring away white patrons, but ended up making more money because of the influx of black spectators eager to see Robinson.

As the Dodgers won games and Robinson continued to play well, he soon became one of the most popular figures in America. TIME magazine put him on its cover. The Sporting News named him baseball’s very first Rookie of the Year. But as his success and profile grew, Robinson took the opportunity to speak out against the injustices he witnessed and experienced. He no longer had to keep quiet. “I was a fine guy,” he said, “until I began to change.”

That transition for Robinson is where part two of the documentary begins. Now that he was an established major league ballplayer — “in the door,” as writers like Howard Bryant put it — Robinson no longer had to abide by the pledge he initially made to Branch Rickey. He could speak out. He had to speak out. This is who he was, as Burns established in the early part of his film. Naturally, some didn’t want to hear what he had to say. But Robinson wasn’t going to squander his fame by not advocating for racial equality.

“A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives,” reads the quote on Robinson’s tombstone.

Becoming more outspoken in baseball, however, was increasingly rankling players, fans and reporters. Robinson argued more with umpires, feeling they were making unfair calls. When asked if the New York Yankees — who had frequently beaten his Brooklyn Dodgers in the World Series — were prejudiced, he pointed out that they had no black players on their roster and very few in the minor leagues. Whatever goodwill Robinson had presumably earned was now being lost, even among fellow black teammates like Roy Campanella. But he was being true to himself.

As his playing days reached their end, Robinson set himself up for life after baseball, taking an executive position with the Chock full o’Nuts coffee company. Though he immersed himself into those corporate operations, Robinson had grander, more important social concerns in mind. His profile was never higher, of which he took advantage to raise money for the NAACP, to challenge black people to fight for their rights and not settle for second-class treatment.

Robinson also began writing a column in the New York Post (along with William Branch), which was nationally syndicated and typically ran in the sports section. Yet Robinson often wrote about social issues, such as lynchings in the South, resistance against school integration in the New York area, and accusations of prejudice against the Boston Red Sox for not having black players on their roster. Additionally, he became more politically active with the 1960 presidential election, supporting Richard Nixon.

#StickToSports? There was no chance of that for Robinson. The era he grew up in, the oppression he faced, and the expectation for him to continue being a pioneer and agent for change regarding race relations in the country — a role he wholeheartedly embraced — forged the man who was far more than a baseball player. He was a civil rights leader. He used his celebrity to influence societal and cultural perceptions, to affect political and business change. Sometimes, that even caused conflict within the black community.

It’s impossible to tell the complete story of Jackie Robinson without delving into this aspect of the man. Robinson’s sports career takes up roughly one of the four hours of this film, which might not appeal to some viewers. But this isn’t just a sports documentary, despite its featured subject. That’s not the kind of storyteller Burns has been throughout his filmmaking career. With Baseball (1994) and Unforgivable Blackness (2005), his Jack Johnson film, Burns has sought to chronicle aspects of America’s history through the prism of sports.

But that story, that history can’t be adequately portrayed without delving into race. There’s no better subject for conveying that part of our history than Robinson. And a four-hour tribute to the man, not the mythology — the barriers he broke in baseball and society, and how important a role his wife played in that entire legacy — absolutely does him proper justice.