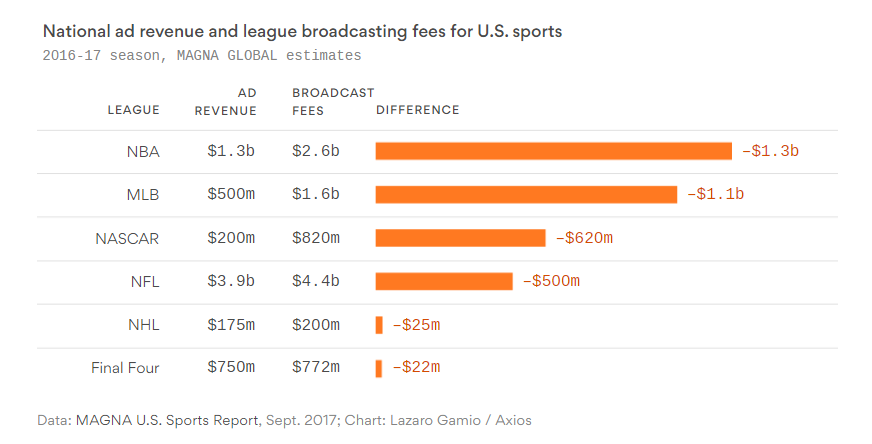

For a long while, there’s been talk of a sports rights bubble and a theory that contracts can’t just keep soaring. That talk was quelled briefly in 2014, when the NBA became the latest league to get a huge boost in its latest rights deal, but that deal itself has received criticism considering ESPN’s trajectory since then, and some executives at that company were even reportedly opposed at the time. And something that may reignite the bubble talk further comes from this Axios story by Sara Fischer on Magna Global’s latest Media Sports Report, which shows that estimates of the ad revenue coming in for major sports are nowhere near what networks are paying in rights fees. Here’s the chart in question, from Axios’ Lazaro Gamio:

Of course, ad revenue estimates alone don’t cover the true bottom line of televised sports. Crucially, cable networks like ESPN, FS1 and TNT charge per-subscriber fees as well (in ESPN’s case, that’s over $7 per month for the main network alone these days), so there’s a dual revenue stream for their sports events. And the high cost of sports rights is often cited as a reason to boost that fee; in particular, ESPN was able to increase theirs significantly after they gained Monday Night Football in 2006. But this helps speak to why more and more sports packages are heading to cable from broadcast; it gets very difficult to make up those rights fees just on ad revenues. (And that’s even more true if the ratings drop, as we discussed earlier this week around the potential $200 million advertising hit for NFL broadcasters from lower ratings.)

And rights fees are just one cost involved in a broadcast. That’s before you get to paying on-air talent and production crews, before you pay for equipment, transportation and lodging, and before you handle all the other expenses that go into putting sports on the air. So expensive rights fees aren’t even necessarily a winning proposition for the likes of ESPN, and that helps explain why many of their executives were leery about the NBA deal.

But, on the other hand, sports aren’t necessarily going to leave the broadcast networks or ESPN soon. Even a sport that isn’t profitable just based on its own broadcasts’ bottom lines can still be valuable. For one, there’s the subscriber fee for cable networks, which need live sports to justify what they’re charging. (And that fee is per network, not per sport.) Beyond that, even financially-unsuccessful programming can be seen as a loss-leader if it helps the network promote other shows. CBS, Fox and NBC do this a lot with their NFL broadcasts to pump up their other non-sports programming, and that also affects the advertising bottom line; they’re presumably not making money for in-house ads, at least not as an overall network). And in the case of the cable sports networks, they need live sports to drive ratings, and having people watch their live sports may lead into some people watching their studio shows.

Another factor to consider in any discussion of a sports bubble is streaming. Companies like Amazon are getting into streaming sports in a big way, including the acquisition of Thursday Night Football streaming rights and a potential bid for English Premier League rights in the U.K. , and they see ways to profit from it. Amazon in particular has an effective multiple-revenue stream model for shows like TNF, selling expensive advertising rights while also making money off the Amazon Prime subscriptions needed to access the stream and off the NFL-associated products they can then sell to those who watched it. So they can afford to toss in a lot of money for sports events they want, and that may help keep prices high even with broadcast and cable networks’ struggles.

However, it should be noted that streaming companies generally haven’t produced events on their own yet, instead paying to pick up TV networks’ feeds. So they’re not necessarily paying a ton to outbid conventional networks only to then have to pay more in production costs. And the bubble talk isn’t unwarranted even with streaming entrants; yes, someone’s certainly going to pay for sports, but the question is if the current record prices will hold up in the next wave of contracts, and we don’t know the answer yet.

In any case, the Magna data is certainly notable, and it helps to illustrate some of the challenges ahead for sports broadcasters. And another part of their report this week discussed how sports audiences (at least on TV) are getting older, something they’ve previously researched. That also doesn’t bode well for advertising revenues, as advertisers are often targeting the 18-49 demographic (or younger); having the average age of the audience above that for many sports may hurt ad prices further. That graphic doesn’t necessarily show “the sports sky is falling,” especially when you consider the per-subscriber fees, but it does explain why more and more sports are heading to cable and/or streaming, and it shows the challenges out there for both broadcast and cable networks.

[Axios]