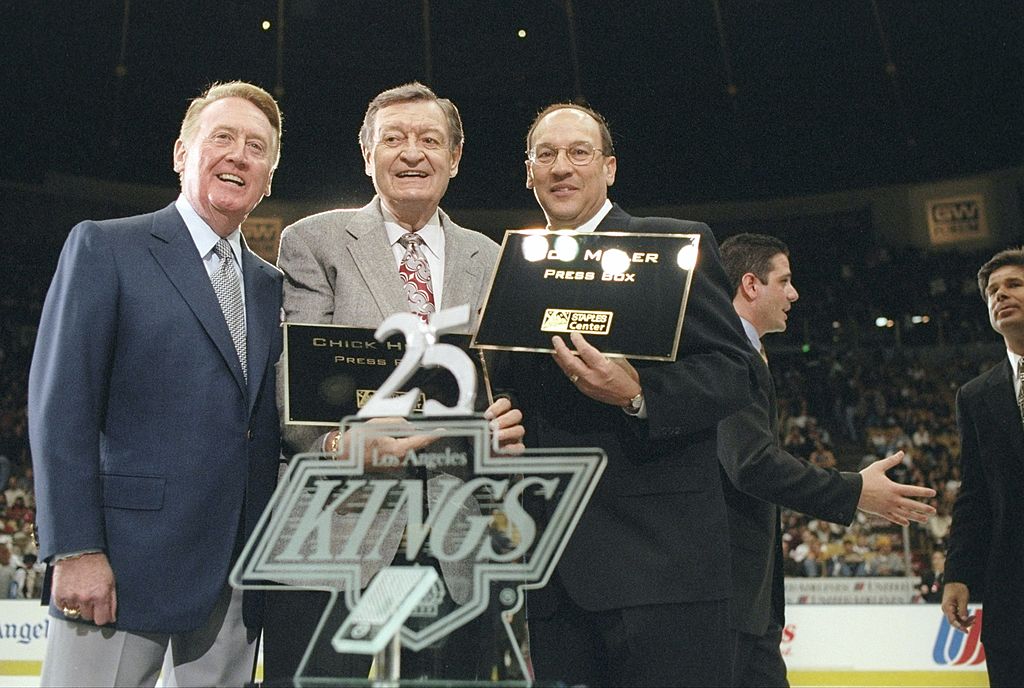

In the year of Vin Scully and on the Sunday of a weekend of Thanksgiving, the broadcast heavens will celebrate one Francis Dayle (Chick) Hearn, born 100 years ago this November 27th.

Hearn was a baby in a cradle in 1916, a handful of years before radio would even hit the airwaves. He reached age 30 when the NBA tipped off and was 43 when the Lakers moved to Los Angeles. But not much later, Chickisms were part of the lingo of the new breed of basketball fans out west. “Like putting a baby in a cradle!” had nothing to do with newborns. It was Chick’s exclamation point on a graceful Jerry West layup.

Hearn returned to his Illinois home from military service after the war and took a job selling pharmaceuticals. One day, the owner of a small radio station in Aurora, Illinois asked him to broadcast a basketball game. “I was pretty good at it and the next day the station’s owner offered me a fulltime job,” Hearn said years later, adding “I was an excellent salesman, married and unsure about taking the risk.” Chick’s father wasn’t too sure either. “Is radio here to stay?” he asked his son. Chick replied, “Dad, I’m following my passion.”

The latest

In 1960, owner Bob Short moved the Lakers from Minneapolis to Los Angeles. The Lakers’ roster was headlined by future Hall of Famers Elgin Baylor and Jerry West, hardly a run of the mill duo. Fans, though, were apathetic. Tommy Hawkins, then a member of the Lakers, schlepped through Los Angeles’ neighborhoods with a megaphone, exhorting the community to support the club.

On radio, the AM dial still monopolized listenership; whether it was news, talk, sports, long form programming or music. The FM band wouldn’t crack the ratings’ score sheet until the early 1970’s. So if a team couldn’t clear an AM station, it was out of luck. The Lakers were out of luck.

Despite finishing the regular season, 36-43, they advanced to the playoffs that first season and beat the Detroit Pistons in the first round. But fans didn’t elbow their way through the turnstiles. Only a few thousand showed up.

Then came the Western Conference Finals against the St. Louis Hawks and owner Short knew he needed an immediate infusion of excitement. With the series tied at two, he finally secured radio coverage. KNX agreed to run the remainder of the playoffs.

By then, March, 1961, after just five years in Los Angeles, Hearn was already known for his high octane USC broadcasts. His lightning quick delivery was unique; a blend of crusader, preacher, quipster, and impromptu critic.

In Southern California, where radio was ubiquitous, Hearn was able to make steak out of chopped liver. He made radios jiggle with his infectious energy and abrupt, self-authored jargon.

Short told his GM, Lou Mohs, “I like Chick Hearn’s flair.” So Short proceeded to call Chick after midnight, the night before game five of the Hawks series and asked him to begin broadcasting the remaining playoff games. Chick flew to St. Louis the next morning, March 27th, and painted an energetic word picture of the Lakers’ 121-112 win. It struck an inspirational chord in Los Angeles. When the Lakers returned home for Game 6, they drew a crowd of some 15,000. Regular season broadcasts began the next season.

Like matrimony, ‘Till death do us part,’ Hearn passed after the team’s 2002 championship, still the Voice of the Lakers. The iconic Los Angeles columnist, Jim Murray, put it best, “Chick and the Lakers were a match made in heaven. Romeo meets Juliet stuff.”

The styles of Hearn and the Dodgers’ Scully were as different as the sports they covered. Hearn’s play-by-play was blended with exultations and sprinkled with lamentations. His broadcasts were a ride on an emotional roller coaster. Scully would always remind himself, “See it with your eyes, not with your heart.”

Hearn wore his emotions on his sleeve and would unflinchingly suggest player trades on the broadcasts at the first sign of trouble. Win or lose, Scully’s mood on-air was undetectable. Hearn’s broadcasts had an edge, Scully’s broadcasts were elegant. Hearn was a showman and Scully a sculptor. Hearn could be brutally unrestrained. Scully was eloquently restrained.

Hearn spewed his words, Scully fondled them. Hearn created a trove of basketball jargon. Scully intoxicated his audience with a rhythmic narrative that made listeners melt. Hearn needed a partner whom he can use as a foil, even Pat Riley. Scully was most comfortable alone. They both sold; one boldly and one subtly. Hearn’s pitch was flashy; Scully’s was seductive, whether it was promoting baseball or a Farmer John hotdog.

Hearn was unpretentious and Scully dignified, Hearn was a charismatic mix of entertainer, cheerleader and prankster and Scully was soothing, gentle and reassuring. “Marge (Chick’s wife) could have made that shot,” Hearn would say. Scully, rarely if ever invoked his wife’s name on a Dodgers’ broadcast.

Both were versatile. Hearn did Bowling for Dollars and Scully hosted a game show on CBS, It Takes Two.

Hearn was the auctioneer, talking a mile a minute and crafting catchy phrases right on the spot. Scully would turn a phrase better than anyone, even if he borrowed it from the basketball court. After a leaping, over the shoulder, upstretching catch by an outfielder against the wall, Scully exclaimed brilliantly and economically, “He goaltended it!”

Hearn didn’t distance himself from players, Scully for the most part did. Hearn announced as a frank, open and invested fan. Scully talked to listeners as his friends.

When Hearn lost his wristwatch on the road one day, he couldn’t let go. On the broadcast that night, the watch was part of the broadcast tapestry. Between passes and baskets, listeners were treated to a live play-by-play of the Lakers game that night and a recreation of Chick’s search for the lost watch that day. “They get it to Worthy. I checked with the restaurant, the watch wasn’t there. Now they get it to Scott, I looked through every drawer in the hotel room, nothing doing! Scott, a three, I knew he would hit it!” As for Scully, no one would know whether he even wore a watch.

As both men aged, they kept mentally sharp on the road. Hearn did crossword puzzles, particularly on game day when he was generally restless. Scully was a voracious reader. Hearn earned the moniker Chickie Baby. For Scully, a man who would quote the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, Vinny Baby is a non sequitur.

Both were blessed with an announcer’s best friend, a team that wins. The Lakers won 9 titles during Hearn’s years on-air and partook in 21 NBA finals. The Dodgers won 6 championships while Scully presided over the booth and played in 13 World Series.

Hearn was all about the action. He didn’t spin flowery yarns during a nonstop basketball game.

Baseball is one thing and football, despite its rhythmic lulls, is another. It has its restraints for a storyteller, even a master like Scully. When he covered the NFL on CBS television, Vin adroitly squeezed in the history behind the nickname of Jack ‘Hacksaw’ Reynolds. But the tale lost its luster when huddles visibly disengaged for the next play from scrimmage. The football canvas wasn’t large enough. The punch line didn’t quite have the schmaltzy Scully feel.

Chick would speak his mind to anyone listening. “Shouldn’t the networks hire someone who knows something about the NBA?” he bellowed in April 1975, in an elevator cab filled with sports fans. It was an obvious shot at Brent Musburger who had been anointed by CBS to serve as its lead NBA voice. Scully was more discreet and prudent.

Early on, Hearn was given the title of Assistant General Manager. Scully never held an official title with the Dodgers. He was simply the team’s refined and polished broadcaster, the voice of Southern California summers. Hearn was the advocate, waving the team colors for a couple generations.

Hall of Fame basketball coach Jack Ramsay walked into a summer league practice one day and chuckled when Hearn had a lanyard around his neck and a whistle in his mouth. Chick was in middle of a gaggle, refereeing a scrimmage. Scully, in umpires’ gear? Doubtful!

Scully will tell you that when he arrived in California, he enjoyed Hearn’s work on USC football and that the acceptance of Chick’s television/radio simulcasts of Lakers games allowed him to do the same with the Dodgers years later.

If there are coaching trees, there are broadcasting trees. Ted Husing was America’s first sportscaster. He shares the same birthday as Chick. Husing influenced virtually all announcers who launched their careers from the pre war years through the 1940’s. The list is impressively long and it includes Hall of Famers Mel Allen, Marty Glickman, Jack Buck and Jack Brickhouse. As a kid, Scully listened to Husing’s football and fell in love with the roar of the crowd. Hearn too was a student of the Husing era.

Al McCoy, still the melodic voice of the Phoenix Suns at age 83, told me in definitive tone, “Marty Glickman helped popularize the NBA in the East in the 1950’s and Chick Hearn did so out West in the 1960’s.” Hearn indeed is the only broadcaster recognized twice by the Basketball Hall of Fame, as recipient of the annual Curt Gowdy broadcast award and as a contributor for helping grow fan interest in the game.

One hundred years after his birth, we can all learn lifelong lessons from Chick Hearn. Yes, talent, energy and creativity are gifts at birth. Yet glittering success comes only though dedication, commitment, preparation, loyalty and passion. Hearn didn’t miss a Lakers’ broadcast from 1965 to 2001. Whether it was an illness or a travel challenge, Chick found his way to the microphone every single night. One day, the team was playing in Houston and Chick’s heart acted up. He was taken to a local hospital where he underwent a blood transfusion. Doctors insisted that he stay in the hospital for observation. Chick would have nothing of it. Strong willed, he proceeded to the arena.

Sports fans can agree that the records of the two men, both once in a century announcers who worked the same market at the same time, might be as indelible as DiMaggio’s. Heck, 3,338 straight Lakers’ broadcasts and 67 years with the same franchise. Not soon!

And lest we forget, November, 29th, a retired Vin Scully turns 89.

As he might say, “Bless his heart.”

David J. Halberstam – halby@halbygroup.com – is the author of Sports on New York Radio: A Play-by-Play History and The Fundamentals of Sports Media and Sponsorship Sales: Developing New Accounts

Comments are closed.