“The Floyd Mayweather vs. Brian Kenny interview was so widely covered in the sports world at the time, that we decided to take advantage of that well-known relationship between the two to create a fun ad for our fans,” said Seth Ader, senior director of sports marketing at ESPN. “The premise of the ‘This is SportsCenter’ campaign is to showcase this fantasy world where athletes, anchors and mascots live and work together in our Bristol, Conn., headquarters, so it made sense to feature them the way we did.”

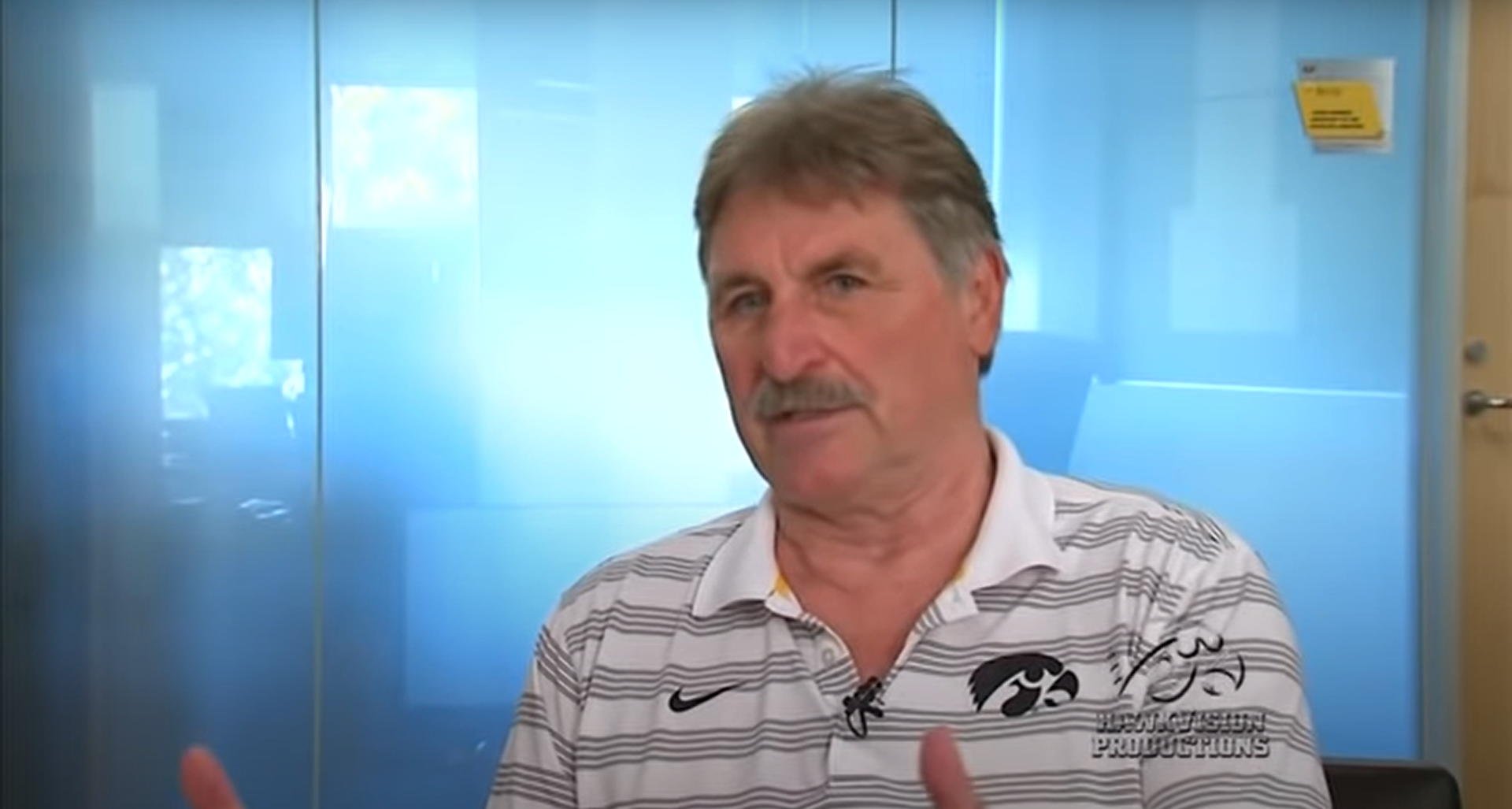

Kenny remembers the commercial segment fondly.

“Funny thing, I show up and he comes in with his people and Leonard and we shake hands and say hello and everybody is having a good time,” Kenny said. “As part of the thing we explain he needs to hit the bag for a few minutes. Then we get to the part where they take a picture of me and they tape it to the bag. He goes, ‘Oh man. Oh yeah. OK, start rolling the cameras. You better start rolling.’ He couldn’t wait to start popping the bag with my face on it. He was a little too eager. We all had a good laugh.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kw9XqiBXKgM

It would take some time before the enormity of the interview would sink in with Kenny. “A little after that, I remember interviewing Charles Barkley on SportsCenter. We had never spoken one on one,” he said. “I was thinking, ‘Introduce myself to Charles, I don’t want to presume people knew who I am. Hopefully this goes well. Charles is a great interview.’ We get a mic check.

“‘Charles, it’s Brian Kenny, great to meet you,’” Kenny recalled saying. “He says, ‘Last time I saw you, Floyd Mayweather was getting all up on your ass.’ I thought, ‘This is going to go fine.’ It has become this icebreaker with other athletes, with fans.”

* * *

Despite Kenny’s best interrogation, Mayweather-Pacquiao, five years later, hasn’t happened. Periodically, before each man’s next fight or slightly after, some writers and fans will flurry anew about whether Mayweather-Pacquiao could be on the horizon. The rest of the writers and fans roll their eyes.

Kenny himself expected, at the time of his interview with Mayweather, that it would happen. He had history on his side. There is no fight that would have made the kind of money Mayweather-Pacquiao could have made that didn’t happen eventually.

Top Rank founder Bob Arum said Mayweather turned down a $100 million purse offer to Pacquiao’s $80 million. Promoters are, by their very nature, prone to exaggeration. But Pacquiao definitely turned down a flat $40 million offer from Mayweather in 2012, not including upside from pay-per-view revenues, which by one estimate would’ve been $160 million. The fight would’ve made more money off ticket sales, sponsorship and overseas rights.

The first round of negotiations began in 2009, and concluded, fruitlessly, in 2010. The two sides agreed to every term except one: advanced drug testing sought by Mayweather, who had become skeptical of Pacquiao’s rapid, successful rise in weight.

There were valid arguments on both sides about Mayweather’s request. Mayweather had insisted Pacquiao would be “easy work,” and that his knockouts of De La Hoya and Hatton paled in comparison to his performances against both men because Pacquiao merely was devouring his “leftovers.” Why, then, was drug testing suddenly a dealbreaker? And Pacquiao’s rise paralleled in part Mayweather’s own physical evolution. As a 16-year-old amateur, Mayweather weighed 106 pounds. When Pacquiao turned pro at age 16, he weighed 105 pounds.

Over time, some of the claims by the Mayweather camp about Pacquiao were comical – uncle Roger would assert that Pacquiao was on something called “A-side meth,” which he helpfully explained that Filipino soldiers used to make themselves bulletproof.

Yet Mayweather’s insistence on advanced drug testing would later prove prescient: Numerous fighters who subsequently underwent something akin to the kind of testing he popularized would test positive. Pacquiao’s various excuses for why he didn’t want the drug testing were inconsistent and flimsy; Pacquiao had a fear of needles, his team said, yet he bore numerous tattoos. As the first round of negotiations dragged out, Pacquiao’s side would try to bridge the gap by proposing testing up to a certain date before the fight – but testing experts said such a cutoff date would be insufficient.

A second round of negotiations, later in 2010, would become so convoluted that Mayweather’s side claimed there were no negotiations at all, only for then-HBO sports president Ross Greenburg to release a public statement acknowledging that he had indeed served as an intermediary for both sides. There were never any serious negotiations thereafter.

* * *

“It’s a dynamic place,” Kenny said about which side was most to blame. “They were both stubborn at different times. I’m not into blaming one guy or the other. I think they both share the culpability. There are times where if Floyd wanted it to happen it would’ve happened. Certainly if Manny wanted it to happen, in the initial negotiations, it was right there. “

The reason it is unlikely to happen now is because Pacquiao suffered two consecutive losses in 2012, one controversially by decision to Bradley and another conclusively to his old rival Marquez, whose knockout of Pacquiao was as savage and frightening as it was historic – few elite boxers have been so violently removed from their senses. Meanwhile, Mayweather signed a six-fight contract with Showtime, departing industry giant HBO, that guaranteed him $200 million over six fights.

“I think when they both need each other financially it might happen, but so far it hasn’t happened,” Kenny said. “Pacquiao’s status in the marketplace has been been diminished by his two losses and Floyd has made a lot of money not fighting Pacquiao.”

And the moment when Mayweather-Pacquiao would have been most interesting has passed. At one point, oddsmakers placed Pacquiao as an 8-5 favorite.

“I think there was about an 18-month period where Pacquiao would’ve made it very interesting and it’s a pick ‘em fight,” Kenny said. “I’ve never once gone into a fight thinking Floyd would lose, even when he fought Diego Corrales, when people were picking against him. And that includes now. Look at the common opponents. Look at how Juan Manuel Marquez couldn’t touch Floyd and he goes life or death with Pacquiao. But when Pacquiao was tearing through De La Hoya and Hatton and [Miguel] Cotto — I think it would’ve been fascinating.”

So where does that leave the sport of boxing?

Since Mayweather’s return in 2009, some fans, casual and hardcore, have turned away from boxing in frustration at its inability to make such an obviously desirable fight as Mayweather-Pacquiao. Opportunities like that are rare. The last time the two best fighters in the world inhabited the same division was 1993, and that fight happened: Julio Cesar Chavez vs. Pernell Whitaker.

Yet boxing also has, at times, thrived by any measure in the vacuum of Mayweather-Pacquiao. In 2013, a fight on U.S. soil – Alvarez vs. Austin Trout – drew a live audience of more than 39,000 fans. And after Alvarez-Trout came Mayweather’s duel with Alvarez that notched more than 2 million PPV buys.

Boxing had a stellar 2013, in fact. The same bifurcation of boxing that contributed to the failure to make Mayweather-Pacquiao – Pacquiao is aligned with Top Rank Promotions, Mayweather with Golden Boy – had by 2013 metastasized into a full blown war, exacerbated by the failed Mayweather-Pacquiao negotiations.

That competition, aided by a realignment of Golden Boy with Showtime and Top Rank with HBO, fueled both companies to put on the best possible shows they could make within their stables, even if it meant risking glamorous records of their top fighters. But as big as the respective stables of Golden Boy and Top Rank are, they are finite. Inevitably, the in-house match-ups would begin to suffer in quality, and they have in 2014.

The labyrinthine politics have, in recent weeks, taken an even more baroque turn. Golden Boy’s CEO is Richard Schaefer, and he has largely led the company during the personal travails of De La Hoya, who did a stint in rehab. Schaefer and Top Rank’s Arum despise one another. Upon his rehabilitation, De La Hoya has since taken on a more active role with his company, and has made overtures toward ending the “Cold War” between Golden Boy and Top Rank. But Schaefer is violently opposed to working with Top Rank, and De La Hoya’s outreach has fractured the earth beneath them; Schaefer said he no longer even has De La Hoya’s cell phone number. As bad as the “Cold War” has been, a “Civil War” that splits Golden Boy in two could further fragment an already fragmented sport.

And most of the other things that have always limited boxing’s growth remain, while new threats have emerged. With only state-by-state governance providing basic regulation of the sport, and voluntary advanced drug testing programs the only alternative, the specter of widespread performance enhancing drug usage hovers above boxing. It is no idle threat.

This week is surrounded by two weekends that remind how easily boxing can go awry. Last Saturday, Marquez defeated Mike Alvarado. Marquez – a man who shares ties between Mayweather and Pacquiao – has taken to working with strength and conditioning coach Memo Heredia, a confessed dealer of PEDs who now says he is reformed. Marquez’s chest was covered in acne, a symptom of steroid use that aroused a fresh round of suspicion about Marquez (whose knockout of Pacquiao followed his affiliation with Heredia).

One of the consensus best fights in the offing for 2014, between light heavyweight champion Adonis Stevenson and fellow knockout artist Sergey Kovalev, recently fell apart. Stevenson, who had risen to U.S. prominence on HBO, the same network as Kovalev, took a bigger monetary offer for an interim fight against Andrzej Fonfara from Showtime – after signing with manager Al Haymon, who advises approximately 70 fighters and had steered most of his fighters to Golden Boy. The coming Saturday brings Stevenson-Fonfara – a debut that likely foils forever the next most coveted fight among boxing fans behind Mayweather-Pacquiao. And just to bring us full circle, Pacquiao signed a contract extension Tuesday with Top Rank through the end of 2016 that many see as the final nail in the coffin for any hopes of a fight with Mayweather.

“Boxing is still thriving in these alternative universes,” Kenny said, reflecting on the failure to make Mayweather-Pacquiao. “Had they had a great fight or two or a trilogy, who knows, it certainly would’ve transcended the sport. That said, I don’t see any one match-up where it didn’t happen and the sport is harmed irreparably. It really does help the sport when the big names get in the ring together, though. Floyd fighting Oscar, Manny fighting Oscar, Canelo fighting Floyd — these are big events. Even Lennox Lewis fighting Tyson eventually. When the mainstream is reminded how good boxing is, boxing is greatly helped.”

There’s a saying commonly attributed to HBO’s Larry Merchant that goes, “Nothing will kill boxing and nothing can save it.” It goes for Mayweather-Pacquiao, too, and the interview Mayweather had with Kenny that simultaneously lifted interest in the sport and laid bare its weaknesses.

For more quotes from Brian Kenny on the Mayweather interview and the sport of boxing, visit The Queensberry Rules.

Comments are closed.